Wednesday, October 11, 1978

THE BIG FIX. Written by Roger L. Simon, based on his 1973 novel. Music by Bill Conti. Directed by Jeremy Paul Kagan. Running time: 108 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning “occasional violence.”

WHERE IS HOWARD EPPIS (F. Murray Abraham) now that we really need him?

Eppis, author of the counter-culture best-seller Rip It Off and a member of the infamous California Four, was one of the 1960s' most colourful campus revolutionaries.

He's credited with some of the movement's catchiest slogans, such as "never trust anyone over 30" and "hey, hey, L.B.J., how many kids did you kill today?" So where was he, when Universal was creating its publicity campaign for The Big Fix?

"Moses Wine, Private Eye," says the year's least informative movie ad line, ". . . so go figure."

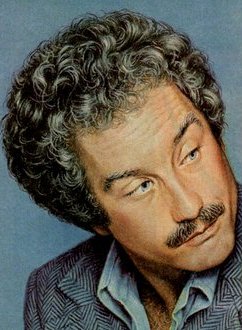

What they neglect to mention is that Wine, as played by Oscar-winner Richard Dreyfuss, is the best thing to happen to whodunits since Sam Spade. The Big Fix is Chinatown for the 1960s generation, a first-class mystery that catches the mood and manner of today.

Wine is the creation of Roger L. Simon, 35, a novelist who thought the time was right for a contemporary private eye. His first Wine story was commissioned by Straight Arrow Books, a subsidiary of — wouldn’t you know it — Rolling Stone magazine.

The movie was directed by Jeremy Paul Kagan, 34, who made his big-screen debut last year directing Henry Winkler in Heroes. His previous credits include the rivetingly original 1975 TV movie Katherine, the Story of a Revolutionary, that starred Sissy Spacek.

Together with co-producer and star Dreyfuss, 29, he is responsible for a fast-paced, totally absorbing whodunit. Not since The Maltese Falcon has there been a more satisfying bit of screen detection.

The Big Fix is the story of Moses Wine and his search for fugitive-from-justice Eppis. Loosely based on Abbie Hoffman, Eppis is the symbol of the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s, a man who disappeared from the public eye years earlier.

His whereabouts become important when, during a California gubernatorial election, posters turn up bearing the aging radical's endorsement for one Senator Hawthorne (John Cunningham).

Hawthorne needs Eppis like Calcutta needs cholera. Wine, a onetime Berkeley activist, is called in to bring his special background knowledge to bear on the case.

It's a frame-up, says Hawthorne campaign organizer Sam Sebastian (John Lithgow). Find out who's behind it.

Wine is hardly what you'd call a hotshot. The 1960s have left him drained. A college drop-out, he's drifted out of a marriage and into detective work with a singular lack of energy.

He's sitting alone one Hallowe’en when his past arrives at the door. Lila Shea (Susan Anspach), an old flame who is now a Hawthorne campaign worker, comes bearing a needed job offer.

They joke, reminisce and reassess one another. "Gotten pretty cynical, haven't you," she says, finally.

"The sixties are over, Lila," he answers, almost wistfully. Neither of them really believe it, though. As the investigation progresses, they rekindle their love.

Director Kagan has divided his picture into two movements. In the first, we meet characters — including Wine’s elderly aunt Sonja (Rita Karen), a delightful old lady who, according to her nephew, “dated every terrorist in Soviet Russia” — are offered clues, and lulled into thinking that this is going to be a lightweight movie.

Then, on the third evening, Lila Shea is murdered. Solving this case of political dirty tricks suddenly becomes a personal mission for Wine. The mood of the movie shifts. The '60s really are over.

A brief newspaper review can do little more than introduce a movie as full and as rich as The Big Fix. Like 1975’s Nashville, it is a picture that will be talked about, written about, analyzed and appreciated for years to come.

Kagan has used the mystery-thriller format to look at the way we — the baby-boom generation — were, and where we are today. What Wine misses about the 1960s, the best years of his life, it is the sense of passion, of commitment, of being able to do something worthwhile.

Simon’s script is a tightly-crafted wonder. Bristling with humour, it drives forward with the speed and power of a Mack truck. Every line, every joke, every aside fits into the pattern of the plot to both etch character and help piece together the complex, central puzzle.

The Big Fix is an exhausting, involving, exhilarating tour de force. Don't go figure, go see.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Decades don’t come in neat packages. For years, I’ve argued that “the sixties” celebrated in pictures such as The Big Fix, was an era that lasted nearly 12 years. It began in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963, the day that U.S. President John F. Kennedy was shot. The end came on April 30, 1975, when the last helicopter took off from the American embassy in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), finally ending U.S. involvement in Viet Nam. In between, the boom generation came of age, some of its members finding their purpose in protest for causes such as peace and civil rights, others choosing to tune in, turn on and drop out.

By contrast, Richard Dreyfuss’s career seemed to express it in a neat package. The actor, whose first credited feature-film appearance was a supporting role in the 1968 teen rebellion drama The Young Runaways, was part of the American Graffiti graduating class. In a film that was of the ’60s (its poster featured the question “Where were you in ’62?”), he played Curt Henderson, a young man setting out on life’s journey. Five years later, in The Big Fix, he was a damaged survivor of that era attempting to come to terms with its meaning.

My assessment of The Big Fix — “a picture that will be talked about, written about, analyzed and appreciated for years to come” — was not shared by enough of my crit-biz colleagues to make it a success. When it failed at the box office, Universal Pictures shelved its plan for a series of Moses Wine pictures.

The Dreyfuss file: The three Richard Dreyfuss features in this package are 1975’s Inserts, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and The Big Fix (1978). His other films in the Reeling Back archive include: 1973’s American Graffiti; The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974); Jaws (1975); Stakeout (1987); Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1990); and Another Stakeout (1993).