Monday, July 26, 1993

POETIC JUSTICE. Music by Stanley Clarke. Written and directed by John Singleton. Running time: 109 minutes. Rated 14 years limited admission with the B.C. Classifier’s warning, "frequent very coarse language, occasional violence and suggestive scenes."

IT OPENS AT THE movies. On the screen, in the reel world of director Alan Smithee's Deadly Diva, we see that sexually aggressive prom queen Penelope (Lori Petty) has a gun. When her late-night rendezvous with wealthy, penthouse-dwelling Brad (Billy Zane) turns sour, she's not afraid to use it.

In the real world of the south central Los Angeles drive-in where the teen thriller is playing, guns are also used. In the movie-within-the movie, we see the young white woman brandishing her weapon at the same time as shots are fired through the window of one of the cars parked to watch it.

Inside the car, a young black man dies. Beside him, his girlfriend Justice (Janet Jackson) screams in horror.

Violent death, John Singleton reminds us, is part of real life in black America. The Oscar-nominated director opened his debut feature, 1991's Boyz N the Hood, with a title card setting out the grim murder statistics in the African-American community.

His new film, the commercially attractive Poetic Justice, begins with the words, "Once upon a time in L.A. . . ." A parable of possibility, it confirms both Singleton's talent and his determination to "do the right thing."

Marketed as a "modern-day street romance," it stars pop performer Jackson in the title role. Named "Justice" in honour of her late mother's law-school ambitions, she copes with her losses by writing poetry.

(Her verse is, in fact, the work of Maya Angelou, the African-American writer asked by U.S. President Bill Clinton to compose and read a poem at his inauguration. Angelou also has a small role in Singleton's film as Justice’s Aunt June.)

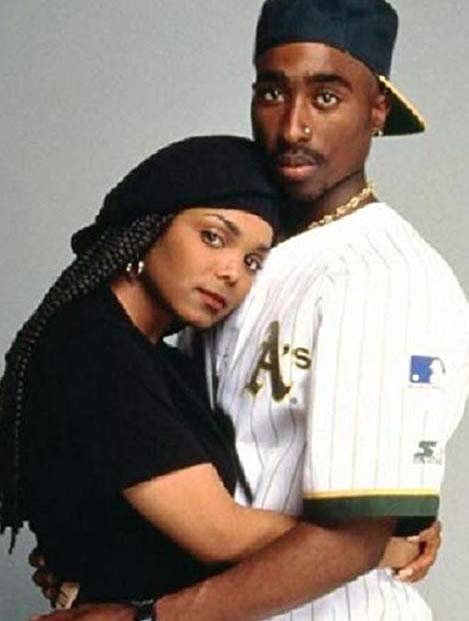

Justice works as a hairdresser for single, self-reliant Jessie (Tyra Farrell), owner of Jessie's Salon De Beaute. It's there she meets an earnest, idealistic postal worker named Lucky (Tupac Shakur, a rap singer who made his acting debut last year [1992] in Juice).

They don't hit it off, but the relationship gets a second chance when Justice's car breaks down, and her best friend Ieshia (Regina King) convinces her to accept a ride to Oakland in a post office van. For reasons never explained, Lucky and his pal Chicago (Joe Torry) take the scenic coast highway rather than the much faster interstate.

In terms of Singleton's narrative agenda, though, it makes perfect sense. He wants to show his two couples from the 'hood (and, through their eyes, the audience) aspects of the dream they've lost sight of.

Following a sign and the smell of "barbecue," they find "the Johnson family reunion." A celebration of extended family, it involves a park full of middle-class blacks, a group that accepts the newcomers without question.

The Johnsons are open, generous and speak standard English without ever once uttering the f-word. “I ain’t seen so many black folks in one place that ain’t no fight,” marvels Chicago.

Further along the road, they discover "the African-American fair," a festival celebrating black culture and tradition. The community’s history, values, purpose and “the dream” are there to be found, Singleton insists.

In the film's foreground are four people working out their personal relationships. A pert rather than a powerhouse performer, Jackson is merely adequate in a role needing real depth.

Ironically, it's her name that will probably bring in the filmgoers that Singleton most wants to see his movie. He provides the expected happy ending and leaves it to them to infer the hard work that’s needed forever after.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1993. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the above review, I suggested that Janet Jackson’s name was the one that would bring in director John Singleton’s target audience. If I had been more in touch with the musical moment, I would have better understood the importance of Tupac Shakur to the movie’s messaging. Considered a central figure in the West Coast hip-hop scene, his reputation as a “gangsta rapper” ran counter to the positive attitude of his character Lucky. Where I was right was in noting Singleton’s message that “violent death . . . is part of real life in black America.” On September 13, 1996, Tupac Shakur died in Las Vegas, the apparent target of a drive-by shooting four days earlier. He was 25.

Less dramatic but no less of a surprise was the death on April 28, 2019, of the 51-year-old John Singleton following a stroke. An obituary that appeared in The Guardian noted that at the age of 22 he was the youngest filmmaker and the first African-American director nominated for a best director Academy Award (for his 1991 debut feature Boyz n the Hood). At the time, critics were comparing him to Orson Welles and Steven Spielberg. Then he made Poetic Justice, a female-friendly film that seemed tepid by comparison. His third feature, the 1995 campus conflict drama Higher Education, had more grit, while his fourth, 1997’s Rosewood, was a sincere recreation of an historic racial outrage. Neither was a boxoffice success. Shaft (2000) was arguably his comeback picture, but rebooting a blaxploitation era film franchise really was a backward step creatively for an African-American director.

Women of colour: Now included in the Reeling Back archive are director Spike Lee’s 1986 feature She’s Gotta Have It, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991), Leslie Harris’s Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1992) and John Singleton’s Poetic Justice (1993).