Thursday, January 24, 1974.

DON'T LOOK NOW. Written by Alan Scott and Chris Bryant. Based on the 1971 short story by Daphne Du Maurier. Music by Pino Donaggio. Directed by Nicolas Roeg. Running time: 110 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some brutality with nude sex scenes.

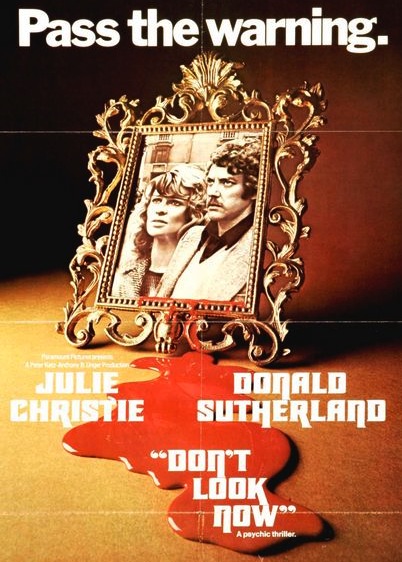

"PASS THE WARNING."

That's what all the promotional posters for Don't Look Now say. Indeed, aside from naming the film's stars — Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie — that's all they say.

So I will.

Be warned, Don't Look Now is a stinker. Unsubtle and contrived, it is an annoyingly pretentious, boringly unimaginative exercise in screen suspense.

The basic story involves a young English couple who become enmeshed in a web of personal tragedy. Based on a Daphne Du Maurier confection, it features Sutherland as John Baxter, an international art-restoration expert, and Christie as his wife, Laura.

It opens with the death by drowning of Christine (Sharon Williams), their eight-year-old daughter, an event that John seems to sense as it is happening. The scene then shifts to Venice, where he is restoring a church.

Laura is still deeply depressed about the loss of their child. Her spirits perk up, though, when they meet a pair of middle-aged sisters, one of whom is blind. Denied normal vision, Heather (Hilary Mason) claims to have a psychic's "second sight," with which she "sees" that little Christine is with them and well.

Despite her pragmatic husband's scoffing, Laura wants to test the blind woman's abilities as a medium. Her persistence is rewarded with a message from beyond warning them to leave Venice immediately.

For New Brunswick-born Sutherland, Don't Look Now is a landmark of sorts. With it, his film career comes full circle.

His first movie appearance, in 1964's Castle of the Living Dead, was an Italian-made horror film. He returned to Italy to shoot the current film, a horror in its own right that heavy-handedly exploits the theme of precognition.

Director Nicolas Roeg, a former cameraman, pays particular attention to his film's visuals, a series of images designed to convey foreboding. His is not the Venice of picture postcards. It is, rather, in the words of one of the film's characters, "like a city in aspic, left over from a dinner party when all the guests are dead and gone."

The city he shows us is a rotting corpse, dank, decaying and honeycombed with dark alleys that harbour a homicidal maniac. As a mood piece, it might have been more effective if Roeg didn't forebode us out before he even arrives in the city.

That feat he accomplishes by overloading his opening sequence — the little girl's drowning in rural England— with ominous cross cuts between the father and child. Psychically!, Roeg practically screams at the audience, the two are linked psychically!

From beyond the grave!, his extreme close-ups bellow, she will call to him from beyond the grave! It is virtually impossible to be subtle after that.

Try as he might, all he can do is confuse the mood. And that's just what he does, throwing in one of the longest bedroom bouts in recent movie memory.

Presumably the couple's love-making is a celebration signalling the end of Laura's despondency. That's never made clear. What is clear is that both performers are playing their first nude scenes for all they're worth.

It goes on. And on . . .

After a while, one becomes awkwardly aware that Roeg is indulging in the same fascination with male nudity that he displayed in his two previous films, 1970's Performance and Walkabout (1971). His camera lingers on Sutherland's body far more than Christie's.

The scene, cross-cut with shots of the couple languidly dressing, contributes to the film's overall instability and incoherence. Throughout, there is the feeling that Roeg will have to justify the shrill buildup with a devastating denouement.

Too bad he hasn't got one.

In the midst of it are two talented performers working hard to make sense out of their singularly ambiguous roles. It's an uphill battle that neither manages to win.

On balance, the best thing about Don't Look Now is a title that I like to think was tacked on as a subtle caution by some truth-in-advertising advocate in the Paramount Pictures organization. Pass the warning.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I mentioned Donald Sutherland's first feature film role (in 1964's Castle of the Living Dead) because newspaper readers in 1974 would have had fresh memories of his Hollywood breakthrough role, playing battlefield surgeon Hawkeye Pierce in Robert Altman's black comedy M.A.S.H. He'd then demonstrated his dramatic abilities in such films as Alan Pakula's Klute (1971), so he was a good choice for the brooding John Baxter character in Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now. The two obviously hit it off because, when his second son was born in February, 1975, Sutherland named him Roeg.

The picture is remembered both as a psychic cinema classic and for the sex scene mentioned in the above review. It prompted a censorship controversy in Britain, and lingering rumours that the performance involved the actors actually doing the deed. (More than 40 years later, all I can say is, "who cares?") Psychics, of course, are a familiar feature on the movie landscape, the central characters in such Stephen King adaptations as The Shining (directed by Stanley Kubrick; 1980) and The Dead Zone (David Cronenberg; 1983). Everybody remembers diminutive actress Zelda Rubinstein's appearance as the "Magic Munchkin" Tangina in Tobe Hooper's Poltergeist (1982) and, yes, Donald Sutherland had second sight as Robert Lees in Bob Clark's Murder by Decree (1979). Finally, here is a link to a YouTube video showing Uri Geller's humiliation on the Tonight Show.