Sunday, March 6, 1988.

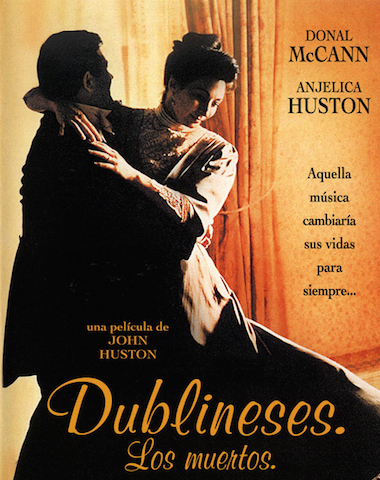

THE DEAD. Written by Tony Huston. Adapted from the 1914 short story by James Joyce. Music by Alex North. Directed by John Huston. Running time: 82 minutes. General entertainment.

FOR JAMES JOYCE, IT was practice. The Dead, the final short story in his 1914 collection Dubliners, was a dress rehearsal for the novel that would make him famous, the celebrated Ulysses.

The two works are similar in their setting, their structure and their mood. Both are set in Dublin in the year 1904.

Both record the events of a single day (January 6 in the short story; June 16 in the novel). Each ends with a bedroom soliloquy.

For John Huston, it was a farewell. The Dead, adapted for the screen by his son Tony and featuring his actress daughter Anjelica, would be the director's final feature film.

A lovingly crafted chamber piece, it records the Twelfth Night celebration at the home of spinster sisters Kate (Helena Carroll) and Julia Morkan (Cathleen Delany). A Yuletide tradition, the party includes recitations and songs, dinner and dancing.

Designated as the evening's host is the sisters' favourite nephew, Gabriel Conroy (Donal McCann). Among his duties is the after-dinner toast, an occasion demanding a speech of bardic eloquence.

A formal, well-mannered chronicle, The Dead offers a glimpse of the Irish urban gentry gathered together for a holiday social. During the evening, we share the anxiety of the elderly Morkans over the obvious inebriation of middle-aged bachelor Freddie Malins (Donal Donnelly) and the appropriateness of political discourse at the dinner table.

We'll see suffragette and Irish nationalist Molly Ivors (Maria McDermottroe) take Conroy to task for his lack of patriotism. Finally, in the chilly depths of the night, we hear Gretta Conroy (Anjelica Huston) quietly tell her husband about passionate young Michael Furey, the 17-year-old country lad who died of love for her a lifetime ago in Galway.

It is this story that prompts Gabriel's soliloquy, a solitary contemplation of his own lack of strong feelings, of life, of love and of the human condition. As he gazes into the darkness beyond his window, he sees "the snow falling upon all the living and the dead."

There is a temptation to see in this decorous mood piece Huston writing his own epitaph, using the introspective Joycean tale to sum up his own rambunctious, often headstrong artistic career.

But, you say, how can one movie possibly encapsulate nearly half a century of film-making, an output that ranged from popular Hollywood studio money-spinners and big-budget prestige pictures to independently-financed personal projects and Canadian tax-shelter schlock?

The answer is: it can't. Its provocative title notwithstanding, The Dead is no Rosebud waiting to offer up the secrets of a public man's private feelings.

Courteous and civilized, Huston's farewell offering is less a testament than an elegant aside. The product of an active lifeforce rather than a man facing the end, it is an example of a professional filmmaker working in Masterpiece Theatre mode.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1988. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Yes, the Missouri-born filmmaker John Huston had connections to the Great White North. Among the questions I posed in my paperback, The Canadian Movie Quiz Book, was to name the movie in which “Humphrey Bogart won an Academy Award . . . for his inspired portrayal of Charles Allnutt, the unshaven and alcoholic Canadian captain of a 30-foot jungle riverboat. Together with Katharine Hepburn, he made war on Imperial Germany on behalf of the British Empire.” The answer, of course, was director Huston’s 1951 adaptation of The African Queen. True trivia fans will remember that the Allnutt character was supposed to have been English, but Huston made him a Canadian when Bogie proved incapable of doing the required Cockney accent.

If that seems like a stretch, I managed a stronger link with a question that asked readers to identify the Canadian father/American son pair: “Walter, the father, was an actor from Toronto. He made his reputation on the stage but he was between tours and working in a Nevada, Missouri power plant when his son John was born. Eventually both of them found their way to Hollywood where John found work as a director. In 1948, each won an Academy Award, the son for directing his father, the father for his acting.” The movie in question was the classic The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, the son’s third feature and his breakout as a major Hollywood presence. Toward the end of a long, varied, always interesting career, John Huston directed his daughter Anjelica to an Oscar win (in 1985’s Prizzi’s Honor).

My book was published in 1979, which happened to be the peak year of Canada’s “tax shelter era.” It was also the year that Huston arrived in Toronto to call the shots on Phobia, that bit of “Canadian tax-shelter schlock” referred to in the above review. Released in 1980, it was a much-reviled boxoffice failure. It’s pretty obvious that he took greater inspiration from the land of his forefathers — Ireland — than from that of his father.

Our Joycean Trio: Director Joseph Strick brought Ulysses to the screen in 1967, then followed it with A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man (1977). John Huston’s adaptation of The Dead came in 1987.

See also: Currently the Reeling Back archive includes an example of John Huston as an actor — director William Richert’s 1979 political conspiracy thriller Winter Kills (1979) — and as a director: his adaptation of Malcolm Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano (1984).