Friday, July 27, 1990.

THE FRESHMAN. Music by David Newman. Written and directed by Andrew Bergman. Running time: 101 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional coarse language and swearing.

THE RESEMBLANCE IS AMAZING.

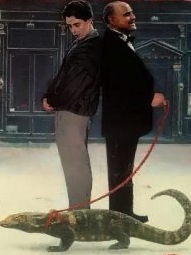

Seated in the deep shadows of Hester Street's Old World Social Club, Carmine Sabatini (Marlon Brando) is a dead ringer for, well, you know who.

Clark Kellogg (Matthew Broderick) sees it immediately. A first year student at NYU's film school, he may be new to the metropolis, but he's no stranger to movie lore.

Broke and in need of money to survive in an expensive city, The Freshman tries not to stare. After all, Sabatini is offering him a job.

Drive out to the airport. Pick up a package. Deliver it to New Jersey.

"For this service," says the elderly Italian importer in his most godfatherly tone, "I'm going to pay you $500."

The Freshman, writer-director Andrew Bergman's sly crime comedy, takes a while getting up to speed. At first, Bergman seems to be remaking Francis Ford Coppola's film-school thesis feature, 1966's You're a Big Boy Now.

At first, Brando's reprise of his own role from Coppola's The Godfather film has the look of a throwaway gag in a one-joke feature. (Bergman's one previous directorial outing, 1981's So Fine, was a single-joke picture. It starred Ryan O'Neal as the distracted inventor of butt-baring designer jeans.)

Here, I'm glad to say, he's just taking the time to establish his characters and their situation. The payoff, when it arrives, is a surprisingly effective comedy about expectations, media images, ultimate loyalties and endangered species.

It's surprising, in that Broderick is a little too old for yet another mixed-up student role. Along with Ralph Macchio and Robby Benson, the 28-year-old actor really has worn out his welcome as an onscreen teenager.

It also comes at a time when we thought that comedies with mob settings were a glut on the market. Brando doing a self-conscious self-parody would not normally be a box-office asset.

The surprise is that it works. Thinking past the obvious, Bergman casts his freshman adrift in a sea of duplicitous, discomfiting illusions.

Within 24 hours of meeting Sabatini's "only daughter" Tina (Penelope Ann Miller), Kellogg learns that they're engaged. And now, men claiming to be from the Justice Department, Fish and Wildlife Division, are chasing him all over downtown.

Things are not what they seem. That Komodo dragon that Kellogg picked up at the airport appears destined for the dinner table at a very exclusive banquet club.

The club membership includes many of the Big Apple's bad apples. Despite his heavy debt to Coppola, Bergman's real inspiration turns out to be screwball comedy and George Roy Hill's The Sting (1974).

The result is a sugar-coated Spike of Bensonhurst, (director Paul Morrissey's 1988 "Family" relations comedy), a movie designed for discussion and analysis in film schools. In the meantime, though, it uses its resemblance to a lot of other films to deliver laughs and provide us with some deft mid-summer fun.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1990. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The passing years have not been kind to Marlon Brando. Once praised as American finest actor, he grew into one of its fattest, a performer famous for reading his lines off cue cards held just out of sight of the camera. In Gary Carey's biography, The Only Contender (1985), Brando is quoted as saying that "acting is the expression of a neurotic impulse. It's a bum's life," later adding that "the principal benefit acting has afforded me is the money to pay for my psychoanalysis." Acting success had come quickly, a four-year-run that included three best actor Oscar nominations — for 1951's A Streetcar Named Desire, for Viva Zapata! (1952) and for Julius Caesar (1953) — and a win (for 1954's On the Waterfront). Brando was less successful handling the demands of success, and went on to play a series of eccentric, undemanding roles until, by the mid-1960s, he'd worn out his welcome with an increasingly sophisticated movie audience.

In 1972, he staged an impressive double-play comeback, starring in Francis Ford Coppola's phenomenally popular The Godfather, and Bernardo Bertolucci's controversial Last Tango in Paris. Older, but apparently no wiser — "The only reason I'm in Hollywood is that I don't have the moral courage to refuse the money," Brando also said — he squandered his second chance with roles in such odd films as Arthur Penn's The Missouri Breaks (1976), Richard Donner's Superman, The Movie (1978) and John Glen's Christopher Columbus: The Discovery (1992). Brando's last "great actor" appearance was in Coppola's landmark Vietnam war film, Apocalypse Now (1979).

The Freshman, the first of Marlon Brando's three features shot in Canada, had Toronto locations standing in for New York during most of the movie. The final two features of his career were made in Montreal. In director Yves Simoneau's 1998 crime comedy, Free Money, Brando co-starred with Donald Sutherland. In The Score, Frank Oz's 2001 thriller, he shared billing with Robert De Niro. It was the only picture in which Coppola's two Vito Corleones (Brando in The Godfather, De Niro in The Godfather: Part II) ever appeared together. One further Canadian content footnote: Marlon Brando turned down the opportunity to visit Toronto for the starring role in director Sidney Lumet's 1977 adaptation of Equus (a part that went to Richard Burton).