Wednesday, December 27, 1989.

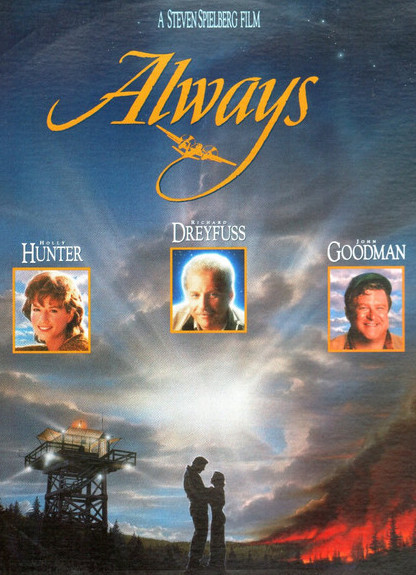

ALWAYS. Written by Jerry Belson. Based on the screenplay for the 1943 feature film A Guy Named Joe, written by Dalton Trumbo. Music by John Williams. Co-produced and directed by Steven Spielberg. Running time: 122 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: occasional coarse language and swearing.

SHE'S THERE FOR PETE'S SAKE.

A real angel, Hap (Audrey Hepburn) knows how to break bad news gently. She's there at the top of a tiny hillock, a park-like bit of greenery miraculously untouched amidst the devastation of a major forest fire.

He's there because, well, there was this other fire in his port engine, followed by an explosion . . . "How did I get out of that one?" waterbomber pilot Pete Sandich (Richard Dreyfuss) asks, at a loss for the answer.

"You didn't," the lady in white says pleasantly.

Though he feels fine, Pete is beginning to realize that things are somehow different.

"Either I'm dead, or I'm crazy."

"You're not crazy, Pete," she says reassuringly.

Call it a Christmas bonus. After all, we've already had a Steven Spielberg feature this year [1989].

In May, the popcorn-picture king's Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade gave the movie industry's billion-dollar summer its running start. Now, with Always, he finishes off the year with a perfectly crafted romantic fantasy.

Two films in one year is something new for Spielberg. But, then, so is Always, the director's first attempt at a classic remake and his first unabashed love story.

For source material, he uses one of his own favourite fantasies, 1943's A Guy Named Joe. A wartime tale in what has been called the film blanc style, it's the story of a bomber pilot who buys it, reports into the hereafter and is assigned to return to earth as a guardian angel.

Never having seen director Victor (Gone With the Wind) Fleming's original, I'm in no position to make comparisons. What I can tell you, though, is that Jerry Belson's updated adaptation of the Dalton Trumbo screenplay works just fine on its own terms.

In Always, the action is set among the fire-fighting flyers of the Pacific Northwest. Dreyfuss, in his third collaboration with Spielberg, brings his own nervy, wisecracking intensity to the role of Pete, the daredevil pilot desperately in love with tomboyish, independent woman Dorinda Durston (Holly Hunter).

When an act of gloriously foolhardy heroism costs him his life, Pete finds himself learning a posthumous lesson in "how it works." According to Hap, the good — "we don't send back the other kind" — return as "spiritus . . . inspiration" to the living.

Pete's assignment is a good-looking, right-thinking young pilot named Ted Baker (Brad Johnson). What Pete doesn't know is that Ted has set his own romantic sights on grieving Dorinda, the woman Pete still considers "my girl."

Always is Spielberg in top form. Its story allows him to combine an obvious love of vintage aircraft with his demonstrated belief in the good will and good humour of higher powers (be they supernatural or extra-terrestrial).

Here, in pursuit of the tale's human dimensions, he deliberately forsakes flashy special effects or the kind of double-exposure imaging standard to films involving ghostly presences. Though unseen by the other characters, his posthumous Pete is fully visible to the camera.

As a result, the focus remains fixed on the interplay of the characters as they sort out their emotions and learn the simple, heartfelt lessons that the best movies have always taught. Always is a holiday treat from a guy named Steve.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1989. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Always is representative of a movie genre known as "film blanc." Coined by Fayetteville State University English professor Peter Valenti in his 1978 Journal of Popular Film paper “The ‘Film Blanc’: Suggestions for a Variety of Fantasy, 1940-45,” it describes the kind of afterlife comedy first seen during the Second World War. Unlike the dark urban realities of film noir, movies in which life is an out-of-control spiral into desperation, crime and betrayal, film blanc is about ultimate redemption. According to Valenti, it began with 1941’s Here Comes Mr. Jordan — remade in 1978 by writer-director Warren Beatty as Heaven Can Wait — the story of a boxer whose death in a plane crash is deemed to be a cosmic clerical error. (Mr. Jordan is the angelic bureaucrat whose job it is to set things right.)

The genre emerged at an ambiguous moment in Hollywood history. In 1941, the outcome of the war was in considerable doubt and, after the U.S. entered the conflict, Americans were experiencing the loss of loved ones overseas. Movies such as A Guy Named Joe were among the ways the popular culture sought to assure the public that their sacrifice was not in vain. Always, Steven Spielberg’s remake, offered its own updated take on the idea that the dead remain with us, and are now in service in a better place. Or, in film theorist Valenti’s words, film blanc shows us a world in which “the forces of light and life (are) triumphant over darkness and death.”

See also: Today we add four incendiary titles to the Reeling Back archive: director John Guillermin’s The Towering Inferno from 1974; Bob Clark’s Turk 182! (1985); Steven Speilberg’s Always (1989); and Ron Howard’s Backdraft (1991).