Monday, January 6, 1975.

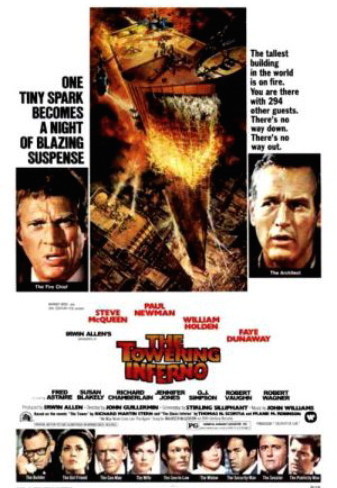

THE TOWERING INFERNO. Written by Stirling Silliphant. Based on the 1973 novel The Tower, by Richard Martin Stern, and the 1974 novel The Glass Inferno, by Thomas N. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. Music by John Williams. Directed by John Guillermin: Running time: 165 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: Parents — could frighten some children.

PUBLICITY TO THE CONTRARY, Irwin Allen did not invent the disaster drama. Audiences were thrilling to tales of life-shattering tragedy and cosmic crisis as early as the 4th century B.C.

Allen's achievement is an economic rather than an artistic one. With 1972's Poseidon Adventure, he demonstrated that his kind of disaster could be a stunning boxoffice success. With it, he became the dominant producer in the current cycle of big-budget movies giving apocalyp-service to character while concentrating on sensational special effects.

Allen, a former Hollywood magazine journalist whose credits include a selection of TV science-fiction series — Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel and Land of the Giants — has always been more interested in crisis than character.

His dramatic innovation has been to make the disaster itself the real star of his shows.

In The Poseidon Adventure, he capsized an ocean liner and his cameras followed a group of trapped passengers as they made their way through the inverted innards of the rapidly flooding hull. Filmgoers loved it.

In The Towering Inferno, he upends his ocean liner and sets it on fire. The new film is built around a blaze that breaks out in a 138-storey skyscraper on the day of its official dedication. Some 300 VIP party guests are trapped half a kilometre above the streets of San Francisco.

There’s no real story. The demands of Allen’s action formula, combined with the circumstances of the film’s production, mitigated against it.

Its script is based on two remarkably similar novels. The Tower, by Richard Martin Stern, was bought by Warner Brothers. The Glass Inferno, by Thomas N. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson, was acquired by 20th Century Fox.

Allen convinced the studios that each of them making the same movie would be foolish. Instead, he proposed that they collaborate on a single super-production, and give him the job of producing it. He promised them another Poseidon Adventure (estimated boxoffice gross to date [1974]: $150 million).

Allen then dropped the two books on screenwriter Stirling (In the Heat of the Night) Silliphant's desk, and asked for some dramatic fuel for his fire. Nothing fancy, just some cardboard and wood.

As a result, there are no real characters. There are some heroes, of course, played by the high-priced help: Paul Newman lopes through his role as Doug Roberts, the architect whose demands for safety features were ignored by the builder's subcontractor son-in-law.

Steve McQueen turns up as fire brigade Captain Michael O’Hallorhan. Indeed, he's the one actor in the piece who threatens to upstage Allen's fire.

Called upon to perform some incredible feats of derring-do, O’Hallorhan responds with laconic sang-froid. He seems to regard the fire's menace as a trivial annoyance.

On the other hand, the hysterical mob around him is a real pain in the neck. Most of the time, McQueen’s character looks as if he’s wishing they’d all just shut up and let him get on with the job.

Dispassionate, almost bored, his attitude is in marked contrast to virtually everyone else in the cast, a group that includes William Holden (as builder Jim Duncan), Richard Chamberlain (Duncan’s cost-cutting son-in-law Roger Simmons), Susan Blakely (Duncan’s daughter Patty), Fred Astaire (con artist Harlee Claiborne), O.J. Simpson (building security chief Harry Jernigan) and Faye Dunaway (architect Roberts’s fiancé, Susan Franklin).

With the exception of Miss Dunaway, who is just leaden, each pumps considerable passion into his or her performance. All the effort seems quite beside the point.

Allen's real stars are the fire and the building, both creations of his special-effects artists. To simulate the 500-metre-high skyscraper, they built a scale model more than 30 metres tall.

Some tricky matte work makes it a believable part of the San Francisco skyline. Equally skilful editing of models, full-scale sets and location footage that includes the Bay city's architecturally unique Hyatt Regency Hotel convince the filmgoer that he is vicariously experiencing an actual conflagration.

That, of course, is the whole idea. A simple storyline ties together more than two-and-a-half hours of progressively more hair-raising situations, as the audience enjoys the raw sensation of being in the middle of incredibly real destruction. And surviving.

Judged by its own amusement-park standards. The Towering Inferno has a slight edge over its most current rival, Earthquake, the year-end's other super-sensation epic. What plot there is ascribes the tragedy to human negligence, a story device that encourages the audience to indulge in a little righteous anger and bloodlust aimed at the guilty parties.

Director Mark Robson’s Earthquake, on the other hand, relies on what insurance companies call “an act of God.” Though better scripted, and generally better acted, it lacks the pulp-novel message-mongering that distinguishes a Silliphant screenplay.

And what is Silliphant’s message? Simply that if builders built better and architects listened to firefighters, he and Irwin Allen would never have been able to ignite their Towering Inferno.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I blame the atom bomb. Once filmmakers realized that apocalyptic events had moved into the realm of scientific possibility, there was no limit to the horrors they could offer up for our entertainment. In the 1950s, science fiction came into its own as a film genre by exploiting our fears of the dire consequences of all the new knowledge. In one screen classic, director Robert Wise’s 1951 feature The Day the Earth Stood Still, an alien ship arrives in Washington to deliver a message to the world’s nations: get your act together or else.

About 20 years into the Atomic Age, having survived one great confrontation — the Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis of 1962 — movie audiences were ready to “stop worrying and love the Bomb.” In 1964, director Stanley Kubrick scored a hit with his comic adaptation of a grim, serious 1958 novel called Red Alert. Screenwriter Terry Southern turned it into Dr. Strangelove, an hilarious heckle of accidental atomic war.

Although our fear of nuclear annihilation may have grown less intense with the passing years, the addiction to mass destruction scenarios remained. In 1970, Hollywood found a new way to play upon our need to always be in harm’s way. Writer-director George Seaton adapted Canadian novelist Arthur Hailey’s 1968 novel Airport to the screen, an all-star production that kicked off a decade-long cycle of disaster movies. The Towering Inferno, with its implicit warning about the safety of tall buildings, is ranked among the best of them.

As noted in the above review, its screenplay was based on two books, one published in 1973, the other in 1974. It’s possible that the novelists were inspired by the 1971 Christmas Day fire in the 22-story Daeyeonggak Hotel in Seoul, South Korea in which 164 persons died. A real life disaster, it remains the deadliest hotel fire on record. Increased public awareness of the dangers inherent in such buildings might have served to avert more disasters. Counterintuitively, they just continued. In 1980, 85 people died in a fire in the 26-storey MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. Another 97 lives were lost in 1986 when the Dupont Plaza Hotel burned in San Juan, Puerto Rico. More blazes are added to the list every year, with 2017 headlines recording 71 deaths in London as a result of the Grenfell Tower fire. In a time of global warming, disasters remain a hot topic for the mass media.

See also: Today we add four incendiary titles to the Reeling Back archive: director John Guillermin’s The Towering Inferno from 1974; Bob Clark’s Turk 182! (1985); Steven Speilberg’s Always (1989); and Ron Howard’s Backdraft (1991).