Saturday, June 2, 1973.

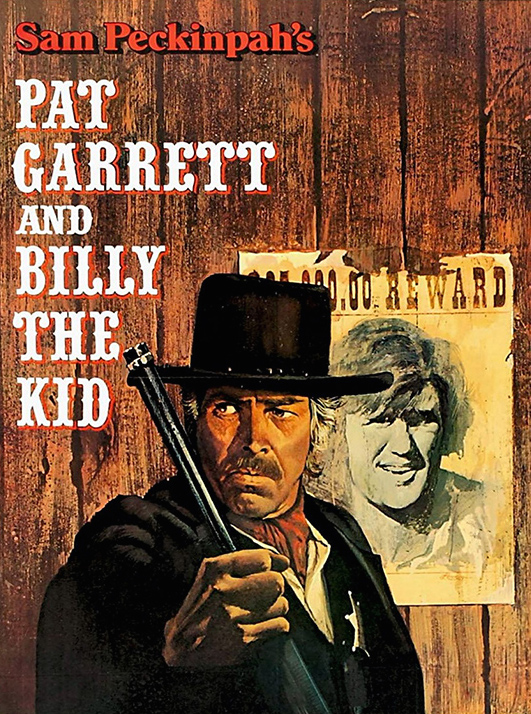

PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID. Written by Rudy Wurlitzer. Music by Bob Dylan. Directed by Sam Peckinpah. Running time: 122 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: frequent violence, coarse language and swearing.

IF I HAD TO SUM UP the new Sam Peckinpah movie in just three words, they would be "watch for children."

Kids are the key. The director's use of them in his films is a consistent clue to the meaning of his violent visions.

Remember the opening of 1969’s The Wild Bunch? As the Bunch, disguised as federal troopers, rides into town, the camera focuses on a group of children happily watching a scorpion that they have forced into a death struggle with a colony of ants.

On its own, the scene could be taken as a simple metaphor, foreshadowing the action of the film. The Bunch is, after all, riding into an ambush.

Kids keep turning up, though — something that has nothing directly to do with either the script or the story. Their presence is strictly a directorial touch.

They are part of the set decoration, silent visual components of a scene, watching with wide eyes, and learning the lessons of survival in a harsh world.

It is as if Peckinpah were saying, "the child is father to the man;" that the violence in American society is the result, not only of the example passed from one generation to the next, but of a natural inclination that is encouraged rather than suppressed.

Remember the apple-cheeked schoolchildren who stood watching the arrival of Dustin Hoffman and Susan George in the Cornish countryside village that is the setting of 1971’s Straw Dogs?

In that film, famous for its final, bloody battle scene, Peckinpah openly questioned the myth of childhood innocence. The battle occurs because the Hoffman character refuses to turn over a suspected child molester to a lynch mob.

The audience, of course, is already aware that the suspect, a harmless, mentally handicapped adult, had in fact been the victim of a cruel joke by the child in question, a little girl who might have clapped her hands in delight at the death of a scorpion.

In The Getaway [1972], Peckinpah's last film, the children are less apparent (actor Steve McQueen is said to have had final cut on that project), but they are there still. Immediately after the bank robbery, for example, Al Lettieri's character shoots the Bo Hopkins character and flings his body from their speeding car. The corpse rolls into a gutter at the feet of a group of children waiting to cross the road.

Maybe Peckinpah is afraid that his point is not getting across. His new movie, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, underscores it almost to the point of parody. The word "Kid" is right up there in the title, and kids are underfoot at virtually every turn.

His opening scene is virtually a reprise of The Wild Bunch. Here, the gunmen are seen plinking at live chickens, with children watching and gleefully carrying off the edible remains.

Later, as the imprisoned Billy awaits execution, children are seen playing on the scaffold, using the noose as a swing.

And so it goes throughout the film. It is a ritual tale, one that is so well known that it hardly bears repeating. Over the years, Billy Bonney has been played by at least 18 different actors in more than 25 films (most recently by Michael. J. Pollard in 1972’s Dirty Little Billy). In half a dozen of them (most notably Arthur Penn's 1958 The Left-Handed Gun, with Paul Newman), the Kid is felled by his old friend, Sheriff Pat Garrett.

A story in which the outcome is obvious has to survive on style, and Peckinpah has plenty of style. His script, by the current "with-it" writer Rudy Wurlitzer, emphasizes the western's mythic element with some fairly heavy-handed confrontations.

The Kid (on learning that Garrett has pinned on a badge): "How's it feel?"

Garrett: "It feels like times have changed."

The Kid: "Times, maybe. Not me."

Peckinpah's deliberate selection of a ritual tale with a heavy overlay of larger-than-life myth is something of a declaration of his artistic independence. His story has no more to do with the historical Billy Bonney than does Hamlet with the Danish royal family.

He emphasizes his points in his offbeat casting: James Coburn as a world-weary Garrett, Kris Kristofferson as a glib and vicious Billy. As they play out their grim ritual, the ripples of their personal pain spread and grow into waves of senseless destruction.

To back up his stars, Peckinpah has assembled a company of familiar character actors, among them Richard Jaeckel, Katy Jurado, Chill Wills, Slim Pickens, Jason Robards, Jack Elam and Elisha Cook, Jr. Few of them are on screen more than a few minutes, but each one makes a solid contribution to the tone and look of the film. .

The most interesting addition to the supporting cast, however, proves to be acting newcomer Bob Dylan. Though Peckinpah trusts him to do little more than stand around and look cynical, his role is pivotal because his character, self-named Alias, is the thematic link between the Kid and the kids.

He enters the picture as a young spectator when the Kid breaks jail. Having no identity of his own — a fact brought out in a two-line conversation with Garrett — he decides to leave his apprentice printer's job and seek out the Kid.

Once he's decided, the ripples of pain begin to spread from him as well.

Peckinpah, perhaps a bit tired of being misunderstood and mislabelled as a simple mayhem-maker, here puts it all out on view. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is his least subtle film to date. It is also a superb cinematic construction job.

It is, at the moment, the best film in town. Watch for children.

* * *

PARTON SHOT: Earlier this year [1973], when Sam Peckinpah's contemporary thriller The Getaway opened at the Capitol, [Province columnist] Lorne Parton and I both turned in reviews, each offering a different viewpoint. In his notice, Lorne predicted that the next Peckinpah film, regardless of subject, would undoubtedly have somebody blasted apart by a shotgun.Well, score one for the fellow in the lower right-hand corner of the page. In his current film, Peckinpah gives Billy Bonney the opportunity to gleefully gun down an antagonist with a scattergun loaded with dimes.

Needless to say, the ever-generous Kid lets his victim keep the change.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I grew up with the Western. The oldest movie genre, cowboy movies began to change in the 1950s as filmmakers felt the need to create a more “adult” Western. In part, they were responding to the challenge of television, which had adopted the genre with unbridled enthusiasm. In part, they were exploring the new possibilities in the old stories of conflict on the nation’s various frontiers. In 1955, the broadcasters upped the ante, launching a TV series targeted at grown-ups, Gunsmoke. Among the talented new writers who contributed scripts to the show was Marine Corps veteran Sam Peckinpah.

In 1961, after serving an apprenticeship directing episodes of such series as The Rifleman and Zane Grey Theatre, Peckinpah made his feature film debut with a frontier adventure called The Deadly Companions. A year later, he generated serious critical acclaim with his elegiac Ride the High Country, a tale of friendship and betrayal that starred Western icons Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott. His next film, the brilliant if troubled Major Dundee (1965), signalled that the ground was about shift under the old genre once again.

It happened in 1967, the year Italian director Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari was released in the U.S. as A Fistful of Dollars. An unofficial remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, Leone’s ultraviolent “spaghetti Western” starred Clint Eastwood, and it changed things forever. In 1969, Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch confirmed his own cinematic genius, and the R-rated examination of frontiersmen facing changing times circa 1913 took its place among the genre’s greatest. Leone and Peckinpah: between them they reshaped our experience of the American West in the movies. And, as Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid showed, Peckinpah had much more to say on the subject.

See also: Today we added four Billy the Kid movies to the Reeling Back archive: the 1966 Billy the Kid versus Dracula; Dirty Little Billy (1972); Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973); and Young Guns II (1990).

Another Sam Peckinpah feature on file is Convoy, the 1978 action comedy that reunited the director with his own Billy the Kid, actor Kris Kristofferson.