Tuesday, August 29, 1973.

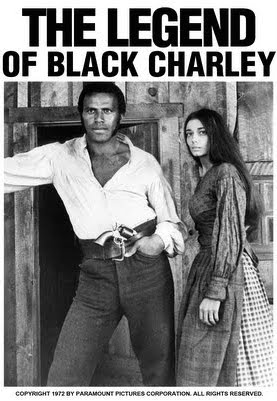

THE LEGEND OF NIGGER CHARLEY. Music by John Bennings. Co-written by Larry G. Spangler. Co-written and directed by Martin Goldman. Running time: 98 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some violence and coarse language.

AMONG THE PRIME CONTENDERS for a bout of future shock are the editors of the U.S. trade paper Variety. In the past few years they've had to relearn the film business, attempting, as they did so, to discover the new nature of the movie audience.

One of the first lessons they learned was that sex sells better than ever, and that the U.S. film market was ready for total candour on the screen. Now, almost every week, the New York-based paper carries plain-spoken trade reviews of the latest “hardcore porno'' (their jargon) available for exhibition in the nation's adult movie houses.

Currently [1973], Variety is noting the presence of an urban black audience that exists somewhat apart from the general mass of moviegoers. Like the moviemakers, they've come to regard the black audience as an economic power, and are now focusing a proportionate amount of their attention in that direction.

Recently Vancouver audiences have had the opportunity to take in such black action pictures as 1969’s The Lost Man, Shaft (1971), and Cool Breeze (1972). There’s been a black western —1972’s Buck and the Preacher — and a black horror film, Blacula (1972), is coming soon.

It may appear that the American movie business has developed a social conscience, but make no mistake about it. Black movies are made because they make money at the boxoffice.

Beyond economics, though, there is a social reality. Black films are, for the most part, underscored with race resentment. Whether justified or not (and, in the case of black America, nothing could be more justified), entertainment films based on resentments are fundamentally exploitive.

Few sentiments are less healthy, or less suited to the development of lasting cinema art. Take the current film, The Legend of Nigger Charley, as one example.

Remove the black factor and, in outline, the story would read as follows: Indentured farm worker, cruelly humiliated and physically abused by his foreman, beats his tormentor to death and flees west. Pursued by a professional bounty hunter, he finally makes a stand and bests the bounty hunter in a gunfight.

His aid is enlisted by a local rancher who is being terrorized by a fanatical preacher and, against the advice of his partners, makes common cause with the rancher. More battles ensue.

Overall, the story is on a par with a typical spaghetti western. Now, colour the hero black. All of a sudden, more than 150 years of pain and injustice are lowered on to the shoulders of the main characters. Under such a burden they cease to be characters, becoming instead representatives of their races.

Instead of being responsible for their actions, the characters — white and black alike — are creatures of circumstance and living clichés. White Southern overseer Houston (John Ryan), is right out of a trashy Kyle Onstott plantation novel.

“Only a man got a right to be free,” he bleats at the long-suffering Charley. “And you ain't a man — you ah NIGGAH.”

Every relationship in the film is forged on a racial basis, the general rule being black equals good, white equals bad. One of the few ambiguous characters in the story, a white sheriff named Rhinehart (Jerry Gatlin), is gunned down by white rednecks for his indecision.

In a gut way, it is deeply satisfying to see Nigger Charley (Fred Williamson) cut a redneck in two with a shotgun. In the end, though, Charley has made nothing but corpses and bred nothing but deeper hatreds. His actions have slaked only the thirst for revenge, not justice.

If the story resembles the violent Italo-westerns, the film’s script and technical credits are only a shade better. Director and screenwriter Martin Goldman comes to this, his first feature, from TV commercials. Many of his camera setups have the painfully contrived look of an extended 60-second spot.

Goldman pays his respects to the small-screen medium in the film's opening sequence, a bit of TV-style footage framed in an almost tube-sized box at the centre of a black screen. Shot with hand-held cameras, it is a news-style record of a slave raid on an African village in 1820.

In it, a pregnant woman is herded along until finally she collapses in labour pains. At the beach, the frame freezes on the face of her newborn babe, and the main feature begins with a full screen, full colour view of the adult Charley.

It's Goldman's best trick, and he uses it up before the titles ever hit the screen. Shortly thereafter the race war starts and, despite his fashionable soft-focus camera technique, Goldman can’t make it look pretty.

* * *

TRUTH IN ADVERTISING: At the moment [August 1972], there are two rather awkward untruths on the theatre advertising pages of The Province. One comes to us through the courtesy of Odeon Theatres and concerns their film The Language of Love, now in its third week at the Hyland Theatre.“We went to the U.S. District Court, the U.S. Court of Appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court,” its ad says, “AND WE WON the right to show you the most sensational film made in Sweden!"

Nonsense. For the present at least, no U.S. court has jurisdiction in Canada. Their picture is being shown on local screens for one reason and one reason only — B.C. film classifier Ray MacDonald saw fit to issue it an approval certificate. Suggesting that American judicial decisions had anything to do with it is worse than misleading. It's insulting.

The second bit of advertising misinformation comes to us from Famous Players, and concerns their new film at the Strand, The Legend of Nigger Charley.

The name of the movie, as it appears on the theatre screen, is the one printed above. The filmmaker, Paramount Pictures (Famous Players' parent company) has issued display posters that carry the same name.

Somebody, though, has decreed that the word "nigger" is to be seen by as few people as possible. This paper carries advertising for The Legend of Charley. Outside the Strand, the marquee announces The Legend of Black Charley.

Again I say "nonsense." Throughout the film the main character is referred to (and refers to himself) as “Nigger Charley.” He cherishes the name with the same fierce pride that a British regiment once felt for the label “old contemptibles,” a name given them by their German enemies.

Excising the genuinely offensive word from the film's title is an act, not of politeness, but of deception. Worse still, it's patronizing, and nobody, regardless of colour, appreciates being patronized.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the introduction to the above review, I emphasized corporate Hollywood’s historic lack of interest in cultural diversity. If covering the film beat taught me anything, it was that movies were made to make money. Since the invention of the motion picture in the late 19th century, its much-honoured arts and sciences have been in service to the entrepreneurs who financed its development, men who cared little for anything other than profits. The business model that emerged consisted of three essential elements.

At one end were the producers, the moguls who ran the “dream factories” where films were made. At the other end were the exhibitors, the showmen who owned and operated the theatres where people paid to see pictures move. Between them, and vital to the commercial venture, were the distributors. Largely invisible to the public, the “distribs” (as they were known in the trade press), insured that the money invested in the “product” generated a tidy profit for everyone involved. The system worked best when its three parts were vertically integrated, with one company (for example, Paramount Pictures) owning the production studio, the distribution company and a theatre chain. In place for more than twenty years, it was supposed to have ended in 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. that such arrangements were in violation of U.S. antitrust law. The American media landscape has changed significantly since then, but that’s another story.

And what does any of this have to do with the arrival of a movie called The Legend of Black Charley on the Strand Theatre marquee? Vancouver, Canada’s Pacific metropolis, did not then have a significant urban black population. Even so, the city’s predominantly white and Asian movie audiences were able to view (and I had the job of reviewing) most of the blaxploitation pictures released during the life of the subgenre. And why was that?

As I pointed out in the “Truth in Advertising” addendum to the above review, U.S. court rulings did not have jurisdiction in Canada. The system of vertical integration that had been upset in the U.S. continued to exist north of the border. Paramount Pictures owned both a distribution arm and Canada’s largest theatre chain (Famous Players). The practice of block booking, a contract that obligated exhibitors to play any and all films released by a distributor, remained the working business model. That meant that the Paramount Pictures feature, The Legend of Nigger Charley, was guaranteed at least a week of screen time in Vancouver, whether or not anybody went to see it. The system pretty much guaranteed that Canadian-made movies would not have access to those screens, limiting any chance for a domestic film industry to compete with the U.S. behemoth. And that, too, is another story.

See also: If the business of the movie business is of interest to you, I suggest that you check out the links to Reeling Back's restoration of my history of the B.C. Filmmaking Industry, published in 2000 in the Encyclopedia of British Columbia. There are eight parts, including: Part 1 [Introduction]; Part 2 [1897-1928]; Part 3 [1931-1938]; Part 4 [1939-1952]; Part 5 [1952-1967]; Part 6 [1968-1977]; and Part 7 [1978-2000]