Monday, January 5, 1976.

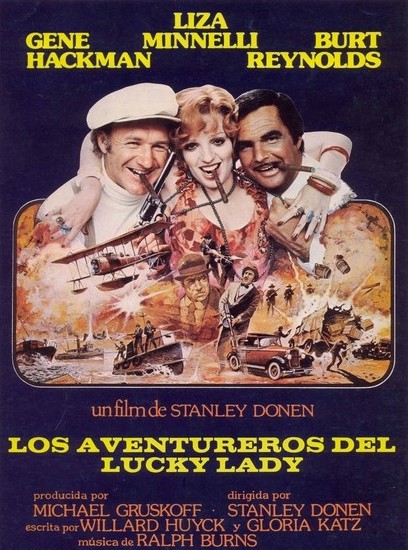

LUCKY LADY. Written by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz. Music by Ralph Burns. Directed by Stanley Donen.Running time: 118 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: occasional violence and coarse language.

IF A BRACE OF hard-working stars and a touch of controversy were the sole ingredients of cinematic success, then Lucky Lady would be a very successful film, indeed. It has both ingredients in spades.

In Gene Hackman and Burt Reynolds it has two of 1975’s most visible male performers. The amiable Reynolds starred in three features last year.

He was seen as an introspective cop in director Robert Aldrich’s Hustle, a down-home con artist in John Avildsen’s W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, and a singing/dancing millionaire in Peter Bogdanovich’s At Long Last Love.

Hackman, too, was on view in three other movies, any one of which could net him an Oscar nomination. He played a troubled private detective in Arthur Penn’s Night Moves, an animal-loving wrangler In Richard Brooks’s Bite the Bullet, and reprised his hard-bitten New York narc “Popeye” Doyle for John Frankenheimer’s The French Connection II.

As for publicity-generating controversy, Lucky Lady has that brouhaha about its ending. As originally written by American Graffiti co-authors Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, the ending was bittersweet and downbeat.

Set in 1930, a year during which the United States was suffering the effects of both Prohibition and the Great Depression, Lucky Lady is the story of three Americans who meet in Mexico.

Claire (Liza Minnelli), newly widowed wife of a Tijuana cabaret owner, is being courted by Walker Ellis (Reynolds), a promoter on the lam from some bad debts. Their plan to make a quick killing rum-running is complicated when a drifter named Kibby Womack (Hackman) forcibly enters their lives.

Together, they enjoy considerable success as liquor merchants and satisfaction as ménage-a-trois lovers. Along the way, though, they develop a powerful enemy in Christy McTeague (John Hillerman), West Coast representative of a nationwide crime syndicate.

The project was handed to Stanley Donen. A director famous for his musical fantasies — 1952’s Singin’ in the Rain, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), The Little Prince (1974)— and romantic comedies — 1958’s Indiscreet and Two for the Road (1967) — he does not, as a rule, favour downbeat endings.

Test screenings of Lucky Lady with alternate endings indicated to Donen that audiences generally agreed with him. Despite the protest of two of its stars (Minnelli and Reynolds) the film has gone into release with a happy resolution.

Creating a lot of peripheral hubbub is one way a film can stand out among the dozen or so Christmas presentations offered every year. For Lucky Lady, it was the only way. Without the controversy, Donen’s film would be a deadly bore.

Despite its great cost — $7 million, $9 million or $13 million, depending on who you believe —Lucky Lady is a collection of machine parts that fail to mesh. Along with the happy ending, Donen seems to have wanted a mood of comedic sentimentality throughout.

To that end, he apparantly directed cinematographer Geoffrey (Murder on the Orient Express) Unsworth to shoot the whole thing through gauzed lenses. The effect is completely at variance with the screenplay’s collection of tough-talking, hard-edged characters, particularly the murderous McTeague.

Further mood problems are created by the film’s almost total lack of flow. Donen’s movie is structured like a musical, in that it consists of a series of set-piece scenes. Like circus elephants, they lumber along with only the most tenuous of tail-to-trunk connections.

As in the traditional Hollywood musical, there is little room for real character development. Filmgoers learn little about Walker or Claire, and nothing at all about Kibby. And yet, we’re supposed to accept it when Donen confronts us with three-in-a-bed as consistent behaviour for the trio.

Ménage a trois is one of the most complex forms of human relationship that a filmmaker can deal with. Few attempt it, so that films such as Francois Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) and Sidney Lumet’s Lovin’ Molly (1974) are among the rare examples.

Not surprisingly, Donen botches it. It's not surprising, because any story so weakly constructed that its ending is optional can hardly support compelling human drama.

The film’s final set piece is a pyrotechnical sea battle, an all-out fight between the forces of good — the independent rum-runners — and the forces of evil, represented by the criminal Syndicate. It should have been a stand-up and cheer event.

It's not.

Because Donen failed to involve me in his plot or his people, that climactic battle had about as much excitement as any cheap chase scene in a drive-in gear-jammer. After that, I couldn't care less how Lucky Lady ended.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Among the most enduring of Hollywood truisms is the one that says screenwriters get no respect. So it was with the talented team of Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, creative partners who connected as film students at the University of California in 1967. They married in 1969 and, three years, later co-wrote and co-directed a low-budget horror movie called Messiah of Evil. Though it made little impact at the time, it achieved cult status in the early 1980s when a Film Comment article called it “one of the top 10 classic, overlooked horror films of all time.” What people did notice was the work the team did for their film school buddy George Lucas, the Oscar-nominated screenplay for 1973’s American Graffiti.

Rather unfairly, that golden moment would be the high point of their lifelong collaboration. The failure of 1975’s Luck Lady put the brake on their momentum, and they wouldn’t be heard from again until the 1979 release of Huyck’s second feature as director, a charming coming-of-age comedy filmed in Paris called French Postcards. Then came another vote of confidence from Lucas, who had appreciated Katz’s (uncredited) advice on his Star Wars project. He called upon them to script 1984's Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the producer’s second Indiana Jones picture (and the picture that brought together director Steven Spielberg with his second wife, actress Kate Capshaw).

That year also featured the release of Huyck’s third directorial effort, Best Defense, a satirical comedy that aimed its comic barbs at American “defense” contractors and their worldwide arms sales. Again, a Huyck-Katz project was the subject of massive studio interference with the final product which, surprise! failed at the boxoffice. In an attempt to rescue his old friend's career, Lucas lent his name (as executive producer), to the Huyck-directed superhero satire Howard the Duck. Well ahead of its time, the 1986 feature became one of the most reviled movies of its decade, as well as a financial failure. Today, in an age of comic-book films, it has taken on cult status.

That experience notwithstanding, Lucas was on board again to produce their Radioland Murders screenplay for director Mel Smith. Although the 1994 film brimmed with period references and performer cameos, it failed to charm audiences. It lost a great deal of money for Universal Studios, and would be Huyck's last feature film credit. The collaborators remained a couple until Gloria Katz’s death in November, 2018.