Friday, June 24, 1983.

TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE. Music by Jerry Goldsmith. Prologue and Time Out written and directed by John Landis. Kick the Can written by George Clayton Johnson, Richard Matheson and Melissa Mathison (as Josh Rogan) and directed by Steven Speilberg. It's a Good Life written by Richard Matheson (from a story by Jerome Bixby) and directed by Joe Dante. Nightmare at 20,000 Feet written by Richard Matheson and directed by George Miller. Running time: 102 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: not suitable for young children; some violence, coarse language and swearing.

The day we stop playing is the day we start growing old.

— Mister Bloom, in Twilight Zone: The Movie

STEVEN SPIELBERG IS THE cinema's Peter Pan. Firmly established as the premier American hitmaker of the 1980s, he has the ability to reach into our cherished memories of childhood and early adolescence.

Like the boy who refused to grow up, Spielberg keeps alive that moment in life when most things are to come and all things are possible. The success of his two previous pictures — 1981's Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) — say that his excursions into the popular culture do indeed speak to the mass audience.

Last Spring, Spielberg donned his producer's cap, gathered together his own crew of Lost Boys and set off for Never-Never Land. Proper children of the first television generation, they knew that once past the second star to the right they would be travelling through another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound, but of mind.

As times change, so does our cultural nomenclature. Peter Pan's dwelling place, a wondrous land whose boundaries are those of imagination, still exists. Only we call it The Twilight Zone.

In many ways, television playwright Rod Serling was his generation's James M. Barrie. Between 1959 and 1963, he stimulated the imaginations of home viewers with 134 half-hour-long visits to the middle ground between light and shadow.

An anthology series, The Twilight Zone carried on the fantasy traditions of such 1930s magazines as Weird Tales. The fact that Serling himself was an Emmy Award-winning dramatist gave the enterprise some superficial class, but the stories, penned by Serling and pulp veterans Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson, were standard pulp fantasy fare.

Set aside the nostalgia element, and TV's Twilight Zone was basically junk. What distinguished it from the other junk on the tube was the fact that it borrowed from the most imaginative, least visited corner of the cultural compost heap, and was aggressively marketed by its creator, a man revered by some, and regarded as a pompous plagiarist by others.

Well, movie serials were junk, too. Spielberg's great talent is his ability to recognize the intrinsic value of a cultural artifact and to remake it, not as it was, but as we want to remember it.

Twilight Zone: The Movie, like last year's Creepshow [1982], is an anthology film. Here, though, each of the segments is the work of a different young director.

Spielberg contributes an episode, as do "Lost Boys" John Landis, the director of 1978's Animal House, An American Werewolf in London (1981) and the current Trading Places (1983); Joe Dante, best known for Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981); and Dr. George Miller, the Australian responsible for the Mad Max/Road Warrior movies (1979/1981).

Together, they have produced a movie that captures the essence of Serling's conception, enhances its strengths, and turns its weaknesses into an intimate joke between the film and its audience.

Their picture begins with a Landis-directed Prologue featuring a car making its way down a lonely highway in the dead of night. A shaggy dog story with a mercifully brisk punchline, it sets the mood perfectly and informs us that we're all here to have fun.

Each of the film's four segments can be described in the single-sentence style of a TV listing:

Time Out (d. Landis) — Outspoken bigot Bill Connor (Vic Morrow) steps through a time warp to become the victim of his own prejudice.

Kick the Can (d. Spielberg) — A group of retirees enjoys a night of restored youth, thanks to mysterious visitor Mr. Bloom (Scatman Crothers).

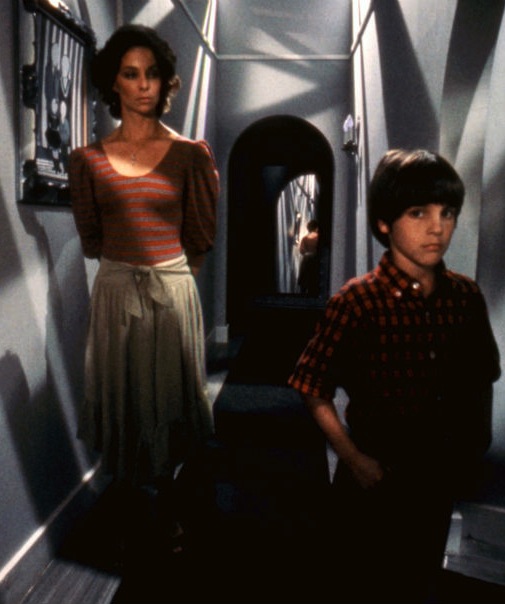

It's a Good Life (d. Dante) — Lonely schoolteacher Helen Foley (Kathleen Quinlan) unwittingly enters the cartoon-like fantasy world of demon child Anthony (Jeremy Licht).

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet (d. Miller) — Nervous traveller Mr. Valentine (John Lithgow) can't convince his fellow airline passengers that there is a hideous creature (Larry Cedar) on the wing, chewing on their jet's engines.

The episodes offer an overview of the original show's various moods, Time Out is the sort of sledge-hammer social commentary that Serling so much enjoyed. Kick the Can, bathed in golden light, is soft-core sentimentality in the Ray Bradbury manner. It's a Good Life is a nicely overwrought, off-the-wall cartoon fantasy, while Nightmare at 20,000 Feet is just a good old paranoid horror show.

The package works because each of the directors is aware of exactly what's needed to get the most out of his episode. Produced with understanding and affection, Twilight Zone: The Movie has fun playing with our recollection of some memorable TV moments.

* * *

A PLATOON OF AMERICAN soldiers breaks through the dense jungle underbrush. Leaderless and afraid, a rifleman is heard to say "I told you guys we shouldn't have shot Lt. Neidermeyer."It's in the otherwise serious John Landis segment Time Out, and the Animal House director is recalling Faber College's martinet ROTC commander, and tying up a loose end. Filmgoers who read the "where are they now?" notes at the end of that 1978 film will remember that Douglas C. Neidermeyer was "killed in Vietnam by his own troops."

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1983. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: At the time of Twilight Zone: The Movie's release, the deaths of actor Vic Morrow and two child extras in a helicopter tragedy was a well-known news story, and hardly needed to be mentioned in my review. Four years later, in my 1987 review of Amazon Women on the Moon, it was worth recalling, because of the involvement of director John Landis in both pictures, and the fact that Landis's nine-month trial on manslaughter charges ended earlier that year with a not-guilty verdict.

Director Joe Dante's Twilight Zone contribution, It's a Good Life, was based on a 1953 Jerome Bixby story, adapted by Serling in 1961 as an episode of the TV series. With characteristic generosity, Dante sought out actor Bill Mumy, who'd starred as Anthony in 1961, to play a cameo role in the film version. The story's animated elements owed much to Dante's childhood ambition to become a cartoonist. As a teenager, he'd written movie reviews for pulp magazine Castle of Frankenstein (1962-1975) before entering an apprenticeship at the informal "school" of Roger Corman. He worked for the legendary penny-pinching producer, editing trailers, before directing such films as 1976's Hollywood Boulevard and Piranha (1978). His love of cartoon reality made Gremlins, released in June, 1984, an an early Christmas gift to Reagan-era audiences, while his appreciation for gimmick filmmaker William Castle turned his period comedy Matinee into a heartfelt celebration of teenaged filmgoing. Animation, genre films, alien encounters and suburban living have all been subjected to his skewed vision. Indeed, as a 2012 assessment of Dante suggests, "his entire career has been a celebration of American cheese." And that's no small compliment if you believe, in the words of author and editor Clifton Fadiman, that "cheese is milk's leap to immortality."