Friday, December 20, 1991.

JFK. Co-written by Zachary Sklar. Based on the books On the Trail of the Assassins (1988) by Jim Garrison and Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy (1989) by Jim Marrs. Music by John Williams. Co-written and directed by Oliver Stone. Running time: 190 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier's warning "frequent very coarse language, some violence."

WE ALL KNOW what happened.

At approximately 12:30 on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963, an official motorcade turned left onto Elm Street in downtown Dallas, Texas. Moments later, shots were fired.

Three (some say four, others six) shots were heard. At least one found its mark, fatally wounding John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States.

(Old news. History. Why am I choking back tears as I write these words?)

We know the what. The question is: Why?

For nearly three decades, that question has obsessed former New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison. Three years after Kennedy's death, he began his own investigation of the tragedy, beginning with a thorough study of the 26-volume Warren Commission Report.

In the late 1960s, Garrison brought criminal charges against Clay Shaw, alleging that the New Orleans businessman had participated in a conspiracy that engineered the death of the president.

Among Shaw's co-conspirators, said Garrison, were Cuban exiles, the mob, big business, the Pentagon, the FBI and the CIA. Warren's conclusion (that the murderous shots were fired by a deranged individual acting on his own) was part of a ritual cover-up.

But why? The same question obsesses director Oliver Stone. In interviews, he refers to the assassination as "the seminal event of my generation. It shaped the 60s."

To understand our history, he argues, we must understand Nov. 22, 1963. Unfortunately, Chief Justice Earl Warren's 1964 report "has been an official myth, the official story for 30 years."

JFK, Stone's "elastic but accurate interpretation" of its meaning, is offered as "counter-myth," an attempt to get at the "true inner meaning of an event."

Stone, creator of such socially engaged dramas as Salvador (1986), Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1998), is back in form. With JFK, the self-appointed conscience of "our generation" has applied his considerable talent to the century's most complex mystery, producing the most daring act of American political cinema since All the President's Men.

We all know exactly where we were when we heard the news.

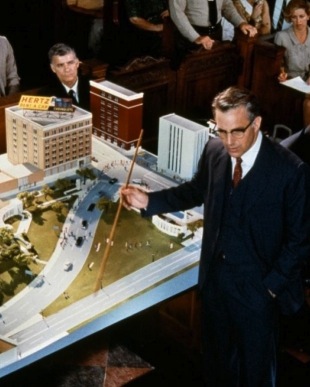

JFK's Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) is in his office. Together with his chief investigator Lou Ivon (Jay O. Sanders), he immediately heads for Napoleon's, a local bar where they have a television set.

Not everyone there views the event as a tragedy. "God," says the horrified D.A., "I'm ashamed to be an American this day"

Shame soon gives way to anger, then dogged dedication. The pattern that takes shape is a frightening one.

"We're talking about the government here," says a member of his staff.

"No," says Garrison. "We're talking about a crime."

The name that Stone gives to this crime is "coup d'etat." In an inspired bit of dramatic fabrication, Garrison meets a retired colonel "X" (Donald Sutherland, playing a character based upon the real-life C.I.A. critic Fletcher Prouty), a former aide to the Joint Chiefs of Staff who eloquently fills in "the big picture."

The result is a great picture. A richly textured combination of docu-drama and blockbuster thriller, it bombards film-goers with more memories, sensations, compelling evidence and star performances than it is possible to take in during a single viewing.

Absorbing and accomplished, Stone's JFK is every bit as important as its director thinks it is. A counter-myth to stimulate the ideals and activism of a new generation, it's a must-see movie for any who remember where they were on that day.

And for our children.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1991. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I can't help but respect Oliver Stone. In describing his film as a "counter-myth," he raised it beyond the reach of critics who might otherwise dismiss it as just another conspiracy thriller, an Executive Action for the 1990s. A politically progressive Vietnam combat veteran, he displayed the same fierce talent in his early films, such as Salvador (1986) and Wall Street (1987). Once in tune with his times — he won Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for Platoon (1986) — he is out of favour in today's surveillance-state America. Stone remains committed to his principles, though, and is an outspoken advocate for beleaguered WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and imprisoned army whistle-blower Bradley Manning. And, given my own pro-Canadianism, I have to add that Stone made his film-making debut in rural Quebec, directing horror veterans Jonathan Frid and Martine Beswick in the nightmare thriller Seizure (1974).

22/11/63 Remembered: Executive Action (1973); Flashpoint (1984); Love Field (1993); Ruby (1992); Winter Kills (1979); Killing Kennedy (2013).