Monday, September 25, 1972

SUPER FLY. Written by Alex Tse. Music composed, arranged and performed by Curtis Mayfield. Directed by Gordon Parks, Jr. Running time: 126 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Drugs, brutality and sex.

THE BLACK MOVIE BOOM continues in the United States, and with it has come a certain amount of discontent. Among those speaking out is ex-footballer Jim Brown, one of the first black matinee idols, and star of Slaughter, yet another urban action film currently [1972] on view in Vancouver.

“We’re on the wrong track with the stuff they're putting out now, with the only emphasis on action and sex,” Brown said earlier this month. "The smart thing to do is for blacks to raise money for black film companies to make films which will ultimately have their major runs in black theatres."

Earlier this year, a group of black businessmen in New York's Harlem did the smart thing, putting together the money to back a black film project. In the director's chair was Gordon Parks, Junior, a professional photographer and son of Gordon Parks, the director responsible for 1969’s The Learning Tree, Shaft, (1971) and Shaft's Big Score (1972).

The result is Super Fly, the story of a ghetto drug dealer with the emphasis on action and sex. The plot line is minimal. At the centre of it is Priest (Ron O'Neal), a cool, stylish "connection” overseeing an empire of 50 street men.

He's not so sure the empire is worth keeping. To his friend and partner Eddie (Carl Lee) he confides his plan for dropping out of the scene, a cool million dollars to the good.

Eddie tries to talk him out of it, at first flippantly — "eight-track stereo, colour TV in every room and a snort of cocaine every day: That's the American dream, nigger" — then quite seriously: "I know it's a rotten game but it's the only one The Man left us to play. That's the stone cold truth."

Priest is unmoved, and the rest of the film is spent putting together his final big deal with the required amounts of action and sex along the way.

And something more.

The more is a sense of honesty and realism that suffuses the film, a sense that director Parks consciously cultivates, and one that owes more to Italian neo-realism than Hollywood slick.

(Twenty-seven years ago [1945], just two months after its liberation, Roberto Rossellini took his cameras into the streets of Rome to film Rome — Open City. The gut issues involved in his story, the apparent authenticity of his actors and locations and his almost documentary camera style combined to create a sense of reality that was soon called neo-realism.)

Parks has tried to give his film the same gritty look and the same authentic ring as the post-war Rossellini.

His actors are virtual unknowns, and, for the most part, they deliver their lines with the low-key passion of sincere amateurs. This, combined with a script that sounds improvised, and sound recording that has a documentary hollowness, shows that his film has a distinctive, if not particularly entertaining, approach.

Parks Junior's major concession to Parks Senior's style is in his musical score. Super Fly's theme is an Isaac Hayes derivative, composed and performed by thin-voiced soul singer Curtis Mayfield.

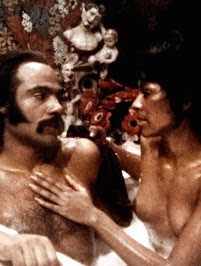

Parks Junior makes one other concession to Hollywood slick. Most of his story is filmed in muted colour tones, as if through a slightly narcotic haze. And then Priest slips into a sudsy bath with his best girl, Georgia (Sheila Frazier)

Suddenly the picture is as crisp and clear as Patton, its style a nod to Russ Meyer rather than Rossellini.

Neo-realism apparently offers no guidelines for the production of fleshy love scenes. And Super Fly, despite its artistic reverse snobbery, couldn't be caught on the modern market without one. It may be that neither Parks Junior nor his film are as honest as they make out to be.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: As noted in the above review, Gordon Parks Junior was following in the footsteps of his father, the Kansas-born photojournalist today remembered as the first African-American to write, produce and direct a major motion picture. GP Senior’s work for Life Magazine made him famous. His debut feature, 1969’s The Learning Tree, was based on his autobiographical novel, the story of a black boy growing up in 1920s Kansas. In his 1973 book Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks, film historian Donald Bogle calls the picture “a lyrical and eloquent statement of the black experience in America.”

Today, movie history buffs are more likely to remember GP Senior for his second feature, 1971’s Shaft. Together with writer-director Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, it is credited with the creation of a black exploitation (or, in Variety-speak, blaxploitation) film genre. Today (June 14), nearly a half-century later, the Shaft family saga continues with a new feature film offering three generations of the New York-based detective clan working a case.

GP Junior eventually followed his father into the film business. At 34, he worked as a cameraman on The Learning Tree. Three years later, he was ready to make his own directorial debut with Super Fly, an independent feature that included GP Senior among its financiers. GP Junior was not involved in the picture’s 1973 sequel — Super Fly TNT was directed by its star, actor Ron O’Neal — but went on to make the 1974 black western Thomasine & Bushrod, the martial-arts thriller Three the Hard Way (also 1974) and an urban adaptation of Romeo and Juliet called Aaron Loves Angela (1975). On April 4, 1979, The New York Times reported that “Gordon Parks Jr., a filmmaker who directed the controversial Super Fly, one of the most artistically and financially successful black‐oriented films of the early 70s, died with three other men when their small private plane crashed on takeoff from Wilson Airport on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya.” He was scouting locations for a new film.

GP Senior outlived his son by 27 years, dying in 2006 at the age of 93.

Black Friday: The four Blaxploitation features recalled in this Reeling Back package are the 1972 features Cool Breeze, Slaughter; and Super Fly along with 1974’s Together Brothers. Other Blaxploitation classics already in the archive: The Legend of Nigger Charley (1972) and Blacula (1972).