Sunday, April 16, 2017

By MICHAEL WALSH

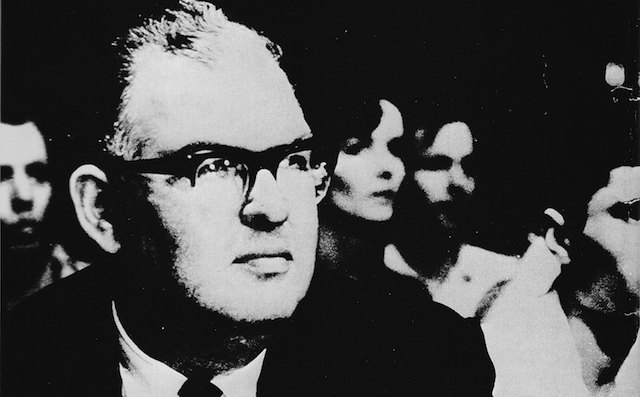

Earlier this month, while adding my 1980 review of Airplane! to the Reeling Back archive, I saw that I had included a mention of theatre critic Nathan Cohen in the piece.

I grew up reading Cohen’s column in the Toronto Daily Star. After posting the Airplane! item, I took my copy of Wayne Edmonstone’s 1977 biographical study Nathan Cohen: The Making of a Critic down from the shelf and reread it. What Cohen proved, Edmonstone concluded, was “that a journalist, working solely within the confines of popular journalism, could become a critic of enormous intellectual influence and, in his own way, one of the architects of our cultural consciousness.”

I was still in high school in February, 1964, the month that Cohen published his “Rules for Budding Critics.” I clipped that column from the newspaper, and have it still.

That fall, I started university. I published my first film review in The Varsity, the U. of T.’s student newspaper, on October 2, 1964. (It discussed a science fiction feature called The Last Man on Earth.)

A clumsy effort, to be sure; it was my first attempt to apply the rules that Cohen set out in this memorable piece:

Wednesday, February 26, 1964.

By NATHAN COHEN

Rules for budding critics

Never forget that the only member of the audience you speak for is yourself.

● ● ●

Always trust your first reaction. Criticism is the act of verbalizing that feeling. Second thoughts, if honest, are usually petty refinements of original impressions.

● ● ●

Don’t hesitate to express yourself strikingly. Who says criticism must be colourless?

● ● ●

Remember that your opinions are worthless unless you provide supporting reasons. Every ignoramus has opinions, and will say them gladly. Your opinions mean something only if you can explain them.

● ● ●

Never worry about what your fellow critics will say. Never worry if they disagree with you. Never worry if they agree.

● ● ●

Artists will tell you: “It is unfair to expect perfection.” It is a plausible argument, but pay no attention. Insist on perfection.

● ● ●

Have enthusiasms. Have prejudices. But if you change your mind, let the reader know without trying to save face.

● ● ●

Never take advice from people in the theatre. Remember, their one goal is to make you one of them. If you must have a bias for anyone in the theatre structure, let it be for the playwright.

● ● ●

Avoid tolerance, a symptom of mental middle-age. It is a weakness that destroys good criticism, and it is insidious. For that reason, never fraternize with theatre folk. If you find that impossible, put friendship aside when you go into the theatre. The result may cost you an acquaintance, but it’s an occupational risk.

● ● ●

If your opinions frequently put you in the minority, accept that some people will impute [sic] your motives, and forget it. In time, they will realize better. And if they don’t, that, too, is a hazard of the job.

● ● ●

Ignore all questions related to the box-office. They have nothing to do with you. Unless you are writing for a trade paper, steer clear of the temptation to foretell how a show will do, financially, after it opens. You are a critic, not a tout.

● ● ●

Do not feel apologetic for liking mass entertainment shows. There is more quality in “Mary Mary” than “After the Fall,” more art in “Barefoot in the Park” than in “Ballad of the Sad Cafe.”

● ● ●

When you get letters, as you will when you become a critic, always look to see if they are signed. If they are anonymous, throw them in the wastebasket, unread. If they are signed, and abusive, wait a week and then compose a temperate and courteous reply. If they are intelligent and well-considered challenges of your notice, answer promptly and fairly.

● ● ●

Never imagine that you have seen your finest production, watched your greatest performance, enjoyed your most satisfying esthetic experience, written your best notice. Never live in the past. Never get lazy.

● ● ●

Don’t pretend to a knowledge you don’t have. It is perfectly possible in some instances to separate a director’s role from his cast’s — when the director is a Kazan or a Guthrie. More often, it’s not. The critic makes a fool of himself when he praises the director for something the actor invented, or censures the actor for something devised by the director.

● ● ●

Avoid technical terminology. If you want to be a play doctor, or a production analyst, get a job with the company. You are cheating your reader.

● ● ●

Don’t be surprised at the amount of trash you are going to be exposed to. It’s the same in all the arts. The worthless is out of all proportion to the worth while. But never relax your war against the conditions which enable mediocrity to flourish.

● ● ●

Turn a deaf ear to special pleaders. You will be told, for example, that shows produced by Canadians should be judged more sympathetically — that is, more leniently — than shows that come from other countries. But the Canadian theatre has never wanted for kindly criticism. That is one of the things that has held it back.

● ● ●

Be sparing with superlatives. Make them meaningful when you use them.

● ● ●

Never comment on the personal and private affairs of performers. That is unpardonable.

● ● ●

Never stop learning. Stay informed on what’s happening in theatre in other lands, and in other arts. And go back regularly to basic sources. There’s still no better book of instruction for a critic than Aristotle’s “Poetics.”

● ● ●

Take criticism of your own work without complaint. A thin-skinned critic is a joke.

● ● ●

Write as clearly as you can, and then, having done so, write your notice again, only more clearly.The above is a Toronto Daily Star column written by Nathan Cohen originally published in 1964. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

The Reeling Back project continues. The most recent additions to this archive include:

SEX, DRUGS & DEMOCRACY — In 1994, a generation before Canada embarked on its own project to legalize recreational cannabis, documentarist Jonathan Blank took a hard look at the tolerant social policies that made Holland stand out in a world that had declared “war” on drugs. (Posted April 16)

JÉSUS DE MONTRÉAL — Daringly conceived and superbly acted, writer-director Denys Arcand’s 1989 feature offers a backstage look at the production of a revisionist Passion Play. His film brims with insights into faith, organized religion and performance art. (Posted April 14)

MATINEE (Midnight Matinee) — Media artist Richard Martin made his entertainment feature-film debut in 1989 with this character-rich variation on the teen slasher flick. Its cast includes many of the best Vancouver actors of the day. (Posted April 12)

MAVERICK — An homage to the 1950s TV hero, director Richard Donner’s 1994 episodic Western comedy stars Lethal Weapon actor Mel Gibson in the title role. It’s only right that James Garner also turns up as a guest star. (Posted April 8)

AIRPLANE! — Starring in this outrageously funny 1980 send-up of the four-film Airport franchise established Leslie Nielsen as a great comic talent and introduced the directorial trio of Jim Abrahams, David Zucker and Jerry Zucker. (Posted April 5)

THE GROCER’S WIFE — Credited with launching Vancouver’s West Coast Wave of the 1990s, debuting director John Pozner’s 1991 independent feature is an “existential love story” set in a post-industrial mill town not far from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. (Posted April 3)

MALAREK — Based on the true story of Montreal investigative reporter Victor Malarek, director Roger Cardinal’s 1988 biographical thriller takes a pulp fiction approach to its tale of urban journalism. Elias Koteas appears in the title role. (Posted March 10)

KING KONG (1976) — The World Trade Centre’s Twin Towers were new to the New York skyline when John Guillermin directed this big-budget remake of the fantasy-adventure classic. Jessica Lange made her screen debut here as the beauty who “killed the beast.” (Posted March 10)

THE VILLAIN — Although Kirk Douglas has the title role in this 1979 live-action cartoon Western, it’s best remembered for introducing the gormless Arnold Schwarzenegger as a screen comedian. Hal Needham provided the vigorous direction. (Posted March 6)

MARIE-ANNE — The story of the first European woman in the Canadian West, director Martin Walter’s 1978 historical drama stars Andrée Pelletier as the fiery force of nature who travelled with her voyageur husband to 19th-century Fort Edmonton.(Posted March 1)

[88]