Sunday, October 19, 1980.

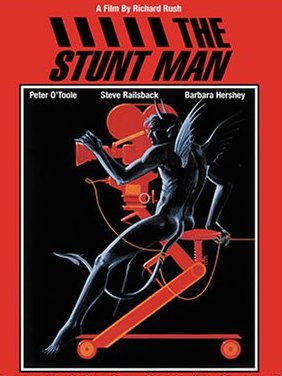

THE STUNT MAN. Written by Laurence B. Marcus. Based on the 1970 novel by Paul Brodeur. Music by Dominic Frontiere. Produced and directed by Richard Rush. Running time: 129 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: not suitable for children; frequent coarse language, occasional nudity and suggestive scenes.

MAGIC. DO YOU BELIEVE in it?

You don't? When you see an ingenious movie like The Stunt Man, try to remember that the screen is blank during half the running time of any film.

Motion pictures don’t move.

Movies are nothing more than a series of still photos set up to flash across a screen in sequence. Every second you see 24 different pictures separated by an equal amount of blank screen time.

You “see” motion because the pictures change faster than the eye's ability to see them individually.

A simple enough trick, really, and yet early filmgoers were awestruck. When U.S. President Woodrow Wilson saw director D.W. Griffith's 1915 feature The Birth of a Nation, he said it was "like writing history with lightning."

Consider, for a moment, the magician at work.

Cecil B. De Mille, a filmmaker given to Biblical themes, once said of the great Griffith that "he was the first to photograph thought." Filmmakers with access to the full technology of their trade possess a power that is almost godlike. They are capable of creation, and it is not unusual for the magicians to become obsessed with their own magic.

Six years ago [1974], director Francois Truffaut picked up the best foreign-language film Academy Award for his La nuit américaine (Day for Night), a movie about moviemaking. Three years later, Peter Bogdanovich took a look at Griffith-era Hollywood in 1976’s Nickelodeon.

You don’t have to be a French auteur or a former film critic to be fascinated with the filmmaking process, though. Former stunt co-ordinator and good ol’ boy Hal (Smokey and the Bandit) Needham turned his camera on the cameras in Hooper, a 1978 action-comedy that starred Burt Reynolds as “the world’s greatest stunt man."

While Needham was making Hooper, action director Richard Rush was filming his own movie-about-the-movies, The Stunt Man. Long delayed, Rush's picture is finally on view, and it is a bit of movie magic designed to delight every audience.

Call The Stunt Man a thriller. It is the story of Cameron (Steve Railsback), a man on the run. We’re not told what he’s done, but there are FBI agents in the posse that’s pursuing him.

During his flight, Cameron witnesses a fatality. An automobile accident, it is, as it turns out, a movie stunt gone sour. He keeps on running, encountering the movie company a second time in a coastal resort town where it is busily filming a First World War battle scene.

Fascinated, Cameron watches the stunt men at work. He exchanges words with the director Eli Cross (Peter O’Toole), who recognizes him from earlier in the day.

Suddenly, the local sheriff (Alex Rocco) arrives on the scene. Cross catches Cameron’s panic reaction. but it is Cross himself who is the object of the lawman's anger.

The sheriff is sure that someone was killed in the auto stunt.

No, says Cross with a flourish. Here is the man you're looking for, he says, pointing to Cameron. Striking an instant, silent bargain with the fugitive, Cross identifies Cameron as “Burt,” the dead stunt man.

Unlike the cerebral Truffaut, Richard Rush is a rock’em and sock’em action director. He put Jack Nicholson on a motorcycle for Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), sent Eliott Gould to college for Getting Straight (1970) and issued James Caan an SFPD badge for Freebie and the Bean (1974). In other words, Rush makes movies that move.

But wait. Critical response to The Stunt Man includes words like "breathtaking” (Playboy), “spellbinding” (L.A. Times), "dazzling” (Variety) and "a work of genius” (Beverly Hills Courier).

No doubt about it, The Stunt Man is brilliant (Vancouver Province). What makes it worth seeing is the fact that Rush manages to weave a fine action-comedy plot through his movie-about-moviemaking to come up with a picture that will entertain and involve you, whether or not you give a damn about his delightful illusion-reality metaphors.

The characterizations and performances are all first-rate. Cross is a director caught in a logical bind. During the Vietnam war, when he wanted to make an anti-war movie, the studios wouldn't let him.

Now that he's able to do it, he's not sure whether there's any market left for his statement. For that matter, he's not sure what his statement is anymore.

Cameron, a genuine Vietnam veteran, recharges Cross's creative batteries. Accepting the moviemaker’s offer of sanctuary, Cameron agrees to become the dead "Burt," and double for the picture's star, Raymond Bailey (Adam Roarke).

He's good. "What have you been feeding that boy,” asks stunt director Chuck Barton (Chuck Bail, a real life stunt director). “Brave pills?”

"It's not what he eats," answers Cross, "It’s what’s eating him.”

Although Cameron understands the terms of their deal, he doesn't understand Cross. “Why are you trying to save my ass?”

"Because,” says Cross, "you are as crazy as the young man I'm making this film about.”

As the work progresses, Cameron sees Cross's godlike powers over his cast and crew. When he becomes involved with the picture’s leading lady, Nina Franklin (Barbara Hershey), he begins to feel that their director's intentions lean more to the satanic.

Cameron suddenly fears for his life.

During the 1960s, a fundamental change took place in the film industry. Happy endings were no longer required. It became de rigeur to reflect reality at its most depressing.

Today, thank goodness, a filmmaker can go either way. You can never be sure how things will come out. In the case of The Stunt Man, the last sound that we hear is Eli Cross laughing because . . .

Do you believe in the magic of the movies?

You will when you see The Stunt Man.

* * *

NAME GAME — Time again to revise your score card (the one without which you cannot tell the players). From now on character actor Allen Garfield will be known as Allen Goorwitz.

Born Goorwitz, the stocky, soft-spoken actor took the name Garfield because he was so impressed with John Garfield's performance in 1947’s Body and Soul. He made his own film debut in the mid-1960s in a sex exploitation film called Orgy Girls.

As Garfield, he’s appeared in nearly 30 feature films, a list that includes 1972’s The Candidate, The Conversation (1974), The Front Page (1974), Nashville (1975), Gable and Lombard (1976) and The Brink’s Job (1978).

As Goorwitz, he continues his career with a role in The Stunt Man. He’s co-featured opposite Barbara Hershey, who was once briefly known as Barbara Seagull. But that's another story.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1980. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: According to the current (December 18) issue of Time magazine, 2017’s Person of the Year is “the silence breakers.” The tipping point may have been an October 5 New York Times report on Hollywood sexual predator Harvey Weinstein. Ten days later, the social media hashtag #MeToo brought together “the voices that launched a movement.” Women of all ages, colours and economic status were mad as hell about the male/female power dynamic, and they weren’t going to take it any more. And Time, in its annual consideration of the person, group, idea or object that “has done the most to influence the events of the year,” tells us that their voice is it. If they stay mad, the result will be serious, permanent social change.

Just because an issue is news doesn’t mean it's new. The phrase “casting couch” has been in use since at least 1931, and the practice of trading sex for stardom seems to be as old as show business itself. There is a particularly telling moment in The Stunt Man when the fugitive Cameron realizes that Nina, the actress he now loves, was intimately involved with Eli Cross. He lashes out, using language that I could not quote in a 1980 daily newspaper review. “What should I congratulate you for?” he says. “The fucking scene, or for fucking the director?”

Nina reacts to his outburst with a lesson in reality. “For fucking the director, honey. Didn't you know that's how little girls get into the movies?” If Cameron didn’t know, he just wasn’t paying attention to 20th century popular culture. In 2017, the sexist culture of male privilege is long overdue for a change. Today, there is a women’s movement that just might make that happen.

TO SEE ALL EIGHT PARTS in Reeling Back's history of the B.C. Filmmaking Industry, follow these links:

Part 1 [Introduction]; Part 2 [1897-1928]; Part 3 [1931-1938]; Part 4 [1939-1952]; Part 5 [1952-1967]; Part 6 [1968-1977]; Part 7 [1978-2000]; Part 8 [Bibliography].