Sunday, September 4, 1983

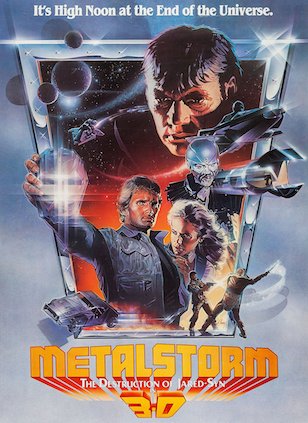

METALSTORM: THE DESTRUCTION OF JARED-SYN. Written and co-produced by Alan J. Adler. Music by Richard Band. Co-produced and directed by Charles Band. Running time: 84 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: some violence.

CHARLES BAND IS AN AMERICAN unoriginal. Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn works so hard recalling other, better, science-fantasy films that it has no character to call its own.

Band, 32, is the son of producer Albert Band, for whom he worked as co-producer and director on this project. If their collective credits prove anything, it is that it is possible for a second generation to move into the business of producing second features.

Band, Senior, gave us such routine program fillers as The Young Guns (1956) and I Bury the Living (1958) before retreating to Rome to produce spaghetti westerns. Band, Junior, is responsible for an X-rated Cinderella (1977) and the quickie sci-fi film Laserblast (1978).

Their Metalstorm resembles nothing so much as an Audie Murphy western from the 1950s. It introduces us to Jack Dogen (Jeffrey Byron), a finder-class Peacekeeping Ranger who is trying to prevent a native uprising on the desert planet of Lemuria.

Causing problems is a self-appointed messiah named Jared-Syn (Mike Preston). Together with his son, a bionic brute called Baal (R. David Smith), Jared-Syn is inciting the nomadic warrior population to take up arms against the local crystal miners.

Band's primary visual inspiration seems to have been the Mad Max movies. Not only does actor Byron resemble Max star Mel Gibson, but he dresses just like him.

Shot within driving distance of Los Angeles, Band's picture shows us a world where everybody rides dune buggies. Although hero Dogen displays a reckless lack of competence, he manages to benefit from the strength-giving love of Dhyana (Kelly Preston), the daughter of a murdered miner; the skills of an alcoholic former-finder named Rhodes (Tim Thomerson), and the loyal friendship of a cycloptic native chieftain named Hurok (Richard Moll).

Like Band's last directorial effort, a post-nuclear-holocaust horror show called Parasite (1982), Metalstorm assembles scenes without much regard for the whys and wherefores of coherent narrative. As in Parasite, Band relies on stereoscopic photography to sell his product.

When that happens, of course, filmgoers should beware. Here, the overall production is no better than another recent 3-D schlocker, Spacehunter. The technical work, while marginally better, hardly makes up for screenwriter Alan J. Adler's ho-hum plotline.

No Mountie, Dogen fails to get his man. As a punishment for him and the audience, Band is now working on a sequel called Journeys through the Darkzone.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1983. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Movies are the Band's family business. Dad, the Paris-born Albert Band, arrived in Los Angeles in 1940, after his parents fled the German occupation. A Hollywood High School graduate, he went to work at Warner Brothers where he learned enough to become an independent writer, producer and director. His directorial debut feature, 1956’s The Young Guns, combined the then-popular juvenile delinquent genre with the western, and launched his career as a successful B-moviemaker.

His youngest son, Richard, had an ear for music and a talent for composition. In 1978, he earned his first feature credit co-writing (with Joel Goldsmith) the score for Auditions, a movie co-written by his dad and older brother Charles. A mock documentary, it recorded the casting process for a porn adaptation of Sleeping Beauty. Since then, Richard has been the soundtrack go-to guy for his immediate relatives and their extended family of exploitation filmmakers.

Albert’s oldest son, Charles, not only inherited the wherewithal to become a writer, producer and director, but he had his own fascination with movie technology. No surprise, then, that he’d be involved with the 3-D revival of the 1980s. Parasite, released in 1982, became a critic’s punching bag, but he returned a year later with Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn, a picture that combined the sci-fi and western genres to turn a modest profit for its distributor, Universal Pictures. It was also a family affair, involving both Albert and Richard.

Still at it, Charles is probably best known for the 14 (and counting) features in the Puppet Master horror film franchise. For 3-D fans, though, his most interesting recent production has to be 2011’s Evil Bong 3D: The Wrath of Bong. The third film in a seven picture (to date) horror comedy series, it follows the adventures of a group of college stoners who encounter a sentient water pipe that messes with their lives. In addition to its enhanced visual effects, Bong 3D provided theatre patrons with scratch-and-sniff cards designed to engage their olfactory sense. “I am a huge fan of William Castle and his ‘emergo’ theatrics,” Band said in a 2011 interview. “So I wanted to create an experience like he used to.”

Sights for two eyes: Today’s 1980s 3-D feature package contains my reviews of director Ferdinando Baldi’s 1981 spaghetti western Comin’ At Ya! and his Treasure of the Four Crowns (1983). Also included are two Charles Band features: the heavily promoted 1982 shock thriller Parasite and his 1983 sci-fi-western Metalstorm: The Destruction Of Jared-Syn.

Binocular visions: Stereoscopic features already included in the Reeling Back archive include director Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 classic Dial M for Murder; Alf Silliman Jr.’s 1969 softcore sex fantasy The Stewardesses; Bruce Malmuth’s 1983 romantic fantasy The Man Who Wasn’t There and Colin Low’s game-changing Expo 86 IMAX short Transitions.