Monday, November 30, 1981.

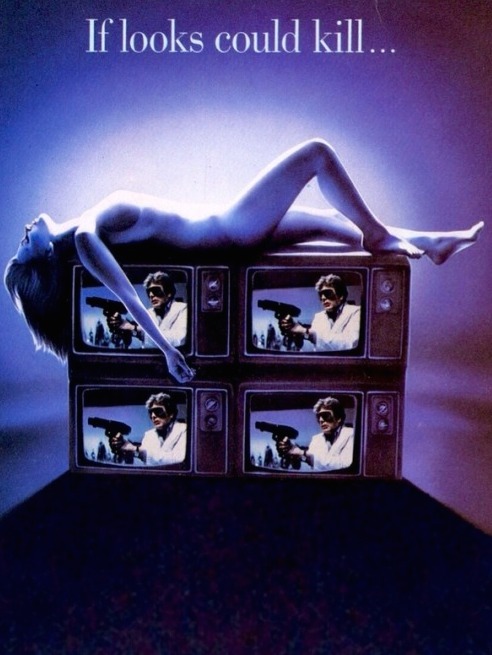

LOOKER. Music by Barry DeVorzon. Written and directed by Michael Crichton. Running time: 93 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Violence and nudity, with occasional swearing.

WHEN JOHN RESTON (JAMES Coburn) speaks, people listen. The head of a $6-billion Los Angeles conglomerate, Reston has a hushed, invitation-only audience for the introduction of his latest technological breakthrough: computer-generated TV commercials that are guaranteed to mesmerize the viewing audience.

“Who could predict,” he says, smiling, “that a free people would spend a fifth of its life sitting in front of a box?" What would happen, he asks, smoothly, if unscrupulous men gained control of the commercial television networks?

There is a picture of Looker writer-director Michael Crichton on the wall above my desk. I keep it there to remind me that there is no such thing as an idea past its time.

Crichton, 39, has become hugely successful recycling well-used concepts and insights. His best-selling 1969 novel, The Andromeda Strain, borrowed a decades-old science-fiction plot in which the Earth is menaced by an alien germ.

Although any number of 1950s thrillers had already beaten that idea into the ground, Crichton’s book was sold to the movies. Filmed under the direction of Robert (Star Trek: The Motion Picture) Wise, it was a 1971 release, and the author’s first taste of cinematic success.

Crichton made his own directorial debut with Westworld, a 1973 thriller that looked as if it had been inspired by a trip through Disneyland’s robot-filled Pirates of the Caribbean environment. Made with considerable visual flair, it too was a hit.

So, never mind that a combination of satellite, home-video and pay-cable revolutions are changing the face of so-called “free television.” Ignore the fact that the power of the commercial networks is rapidly declining, and you might find the insidious conspiracy at the heart of Crichton’s latest screen project mildly disconcerting.

Industrialist Reston, as you must have guessed, is our villain. The good guy is Dr. Lawrence Roberts (Albert Finney), a Beverley Hills plastic surgeon who begins to suspect that life is less than perfect when a police lieutenant named Masters (Dorian Harewood) tells him that two of his recent female patients have met violent deaths.

A quick study, Roberts realizes that the dead women have something in common with two still-living ones. All four were beautiful models who came to him with precise "shopping lists” — computer printouts that indicated what changes needed to be made to make them "perfect.”

Too late to prevent the death of the third girl, Roberts vows to save number four, television commercial actress Cindy Fairmont (Susan Dey). Giving free rein to his penchant for aggressively stupid comic-book heroics, the doctor eventually stumbles upon a secret weapons project as well as some Doonesburyesque political machinations.

Crichton manages to have some fun making fun of TV commercials, and to fill Reston’s sinister speech with some deliciously nasty ironies that might have been truly horrifying in, say, 1959.

Unfortunately, he gets so involved in all of the high-tech set decoration that he forgets that the picture’s plot is supposed to hinge on a murder investigation. He never bothers to explain how four career-conscious mannequins threatened the malefactors’ conspiracy, or why it was necessary to kill them.

Its anti-television posturing notwithstanding, Crichton’s picture is perfect made-for-TV fare. It offers colour, noise, movement and an air of self-importance without the burden of sense, content or originality.

In other words, there is nothing there to get in the way of the salesmen, or their “important” messages.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1981. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In 1984, media theorist Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death, a scholarly essay subtitled Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. At first, I thought his book was about Michael Crichton, a storyteller who specialized in deadly tech. (I was not the only one to make the connection. In a 2016 posting to the German language Zeit Online website, Stanford University professor Adrian Daub noted that Crichton's 1973 movie Westworld “was a kind of pre-study for Jurassic Park,” a film that asked “the Neil Postman-style question of what our addiction to pleasure does to us.”)

Something of a jeremiad, Postman’s book argues that new information technologies — especially television — reduce politics, news, history, and other serious topics to entertainment. Crichton, in his most famous techno-thriller novels and movies, says essentially the same thing. And, for the most part, his dark fantasies resonated with readers. As Guardian feature writer David Smith pointed out in a 2006 profile: “He is no prose maestro, but can match anyone at hitting the public's sweet spot, having sold more than 150 million books and seen 13 of them turned into films.” What I most liked about the Chicago-born Crichton was his fearlessness in identifying real ideas, both new and used. What left me disappointed was the timidity of the movies in which they were presented.

Behind the camera: The four Michael Crichton-directed features posted to the Reeling Back archive today include his 1978 medical thriller Coma, the 1979 historical adventure The Great Train Robbery, the 1981 media mystery Looker, and the 1989 courtroom drama Physical Evidence.

See also: Films written and directed by Michael Crichton currently in the Reeling Back archive include 1973’s Westworld and Runaway (1984). Films based on Crichton works include director Stephen Spielberg’s 1993 adaptation of Jurassic Park, and Richard Heffron’s Futureworld (1976).