Tuesday, July 30 1974.

THE WHITE DAWN. Written by James Houston, Martin Ransohoff and Thomas Rickman. Based on the 1971 novel The White Dawn: An Eskimo Saga by James Houston. Music by Henry Mancini. Directed by Philip Kaufman. Running time: 110 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some scenes of Eskimo life and culture with some nudity.

LOOMING AS ONE OF the issues of the 1970s is the question of Arctic ecology. There are those who argue that uncontrolled exploitation of far northern oil deposits will do irreparable damage to the physical environment.

In presenting their case, conservationists take no comfort at all from the fact that irreparable damage has already been done to the region's social ecology. Like the Indian before him, the Eskimo has seen his traditional way of life altered beyond all recognition.

Mirroring this particular human tragedy in dramatic microcosm is The White Dawn, a sensitive, refreshingly unpretentious study of cultural collision. The film is based on James Huston's novel which is, in turn, based on a said-to-be-true Eskimo legend.

Set in the year 1896, the story begins with the wreck of a small whale-hunting boat in the ice off Canada’s Baffin Island. With no way to return to their ship, the seamen begin a desperate search for shelter.

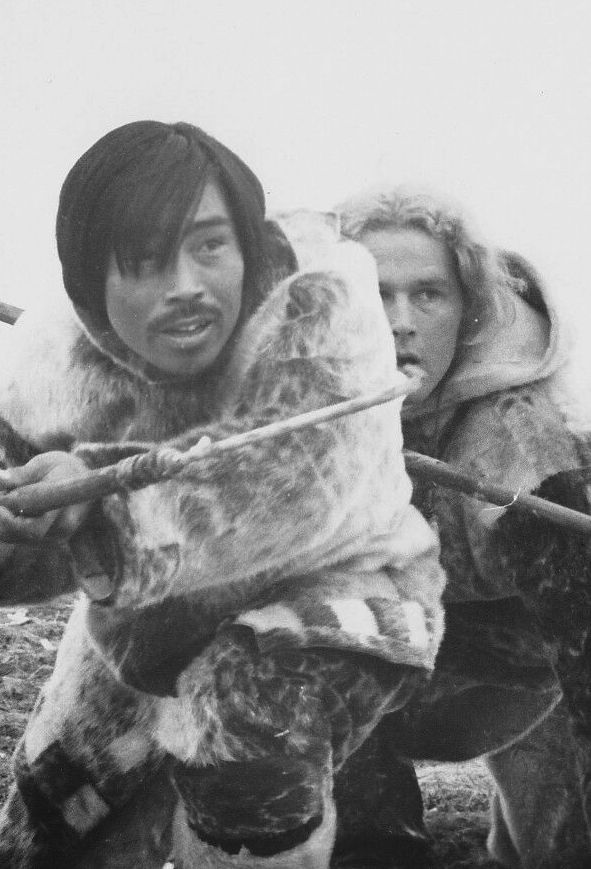

They are found by a young Eskimo hunter named Kangiak (Joanasie Salamonie). Of the original six-man party, only three are still alive when help arrives from the village of Kangiak's father, Sarkak (Simonie Kopapik).

With a natural humanitarianism, the Eskimos gather up the foundlings and rush them to the safety of their camp. The attitudes of the two groups foreshadow almost certain tragedy.

The native Eskimos, an extended family numbering about 14, accept the newcomers as fellow human beings and make them welcome. The white whalers, on the other hand, regard their benefactors with suspicion, thinking initially that they are in the hands of savages.

Firm in this belief throughout is Billy (Warren Oates), who thinks that they are prisoners and is obsessed with the idea of escape.

More flexible is the youngest crewman, Daggett (Timothy Bottoms). At an age where ideals often come into conflict with reality, he is open to new ideas and is frankly fascinated with the logic, efficiency and straightforward honesty of the Eskimo lifestyle.

In the swing position is Portagee (Lou Gossett), a black West Indian. He, too, finds the Eskimo way of life attractive but, like Billy, feels the need to escape to a more hospitable climate.

The whalers live with the arctic band for more than a year, and both groups experience severe culture shock. The film’s sympathy, though, is clearly with the Eskimos.

When director Phil Kaufman set out to film The White Dawn he was, to a large extent, blazing new trails. Of the three existing features on Eskimo life, two were documentaries rather than dramas.

In 1922, pioneer filmmaker Robert Flaherty shot his Nanook of the North on the east coast of Hudson’s Bay. Ten years later, director W.S. Van Dyke travelled to northern Alaska to shoot a docu-drama called Eskimo.

The only completely fictional film to deal with the Eskimo way of life was Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents. Made in 1954 in England and Europe, it starred Mexican-born Hollywood actor Anthony Quinn and Japanese actress Yoko Tani as a native hunter and his wife.

In the case of The White Dawn, author Houston, who worked on the project as an associate producer and co-scriptwriter, wanted to use real Eskimos in the film's key roles. Kaufman was dubious but, after running a series of auditions, decided to go with an all-Eskimo supporting cast.

“They turned out to be simply the best natural actors I've ever encountered," he has since said. At the film's Ottawa premiere, he told Prime Minister [Pierre] Trudeau, who attended with Mrs. Trudeau, that the government should promote Eskimo dramatics.

In Kaufman’s film, they recreate the nomadic lifestyle practised for thousands of years through to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Particularly effective are the Eskimo principals, Kopapik, Salamonie and Pilitak.

As the village elder Sarkak, Kopapik makes the decision to take the whalers into their community, and puts his prestige on the line against the regional shaman (Sagiakotok). They become part of his extended family, sharing his food and, occasionally, his wives.

Salomonie, in real life an artist and adult education co-ordinator, plays his son Kangiak, the hunter who finds the whalers, and who makes Daggett his brother.

The young sailor warms quickly to life on the tundra, especially after Sarkak generously offers to share with him the companionship of his lovely young wife Neevee, played by Pilitak, a northern newspaper editor and CBC broadcaster who is also known as Ann Hanson.

Together they have made an unusually fine motion picture. Even-tempered and low-key, The White Dawn pays tribute to people who were splendidly equipped to survive in isolation, but unready to deal with a perfidious “civilization.”

* * *

ESKIMOS RATED: Afraid perhaps that the sight of several semi-clad Eskimo girls might start a new wave of northward migration, U.S. film classifiers rated The White Dawn R (for Restricted). In B.C., the film is rated Mature. Filmgoers concerned about such things will want to know that besides mate sharing, Eskimo culture includes hunting and the explicit slaughter of such animals as a polar bear, seal and walrus.The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: At the time, we called them Eskimos. In 1971, when James Houston published his novel The White Dawn: An Eskimo Saga, it was the word that North America’s non-native peoples used to describe the First Nations who lived in the far north. A Canadian artist and author, Houston spent 12 years in the Quebec Arctic, and his book was written to pay tribute to Eskimo society and culture. Director Philip Kaufman’s movie adaptation, filmed on Baffin Island, was reasonably faithful to the author’s intent.

In 1977, the region’s indigenous peoples, a group that included delegates from the United States, Canada and Greenland, gathered in Barrow, Alaska, for the first Inuit Circumpolar Conference. The result was the formation of an Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC). Its charter, signed in 1980, defined the Inuit as “indigenous members of the Inuit homeland recognized by Inuit as being members of their people.” The word “Eskimo” is never mentioned, a signal that the term had fallen into disrepute.

In 1978, a linguistically-savvy Québec anthropologist named José Mailhot published a paper that traced the origin of the word to an Algonquian term. Adopted by French traders, it’s considered by some to be derogatory, and Canada’s famously sensitive federal government stopped using it shortly after the ICC made its position on the word clear.

Forty years later, the Canadian Football League’s Edmonton Eskimos have no plans to change the team’s dodgy name. Founded in 1949, the sports franchise “consulted” with “local residents, politicians and cultural leaders” in Yellowknife and Inuvik in May, 2018. Not invited to take part in those conversations was Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, an organization that represents some 60,000 Inuit and is on the record as considering the term racist. The issue continues to simmer, with the team owners said to have a Plan B ready should the real opinion-makers — the season-ticket holders — become uncomfortable with an increasingly controversial brand.

Something of an outlier among Hollywood studio releases, The White Dawn did not set off a wave of Inuit-themed moves. The hero of 1983’s Never Cry Wolf benefits from the counsel of a wise Inuit elder, but it wasn’t until 1992’s Shadow of the Wolf (1992) that the focus returned to the Inuit way of life. Then, in 2001, a Canadian picture called Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner made history as the first feature film written, directed and acted entirely in the Inuktitut language. Notable since then have been the 2008 Québécois director Benoît Pilon’s feature Ce qu'il faut pour vivre (The Necessities of Life), the story of an Inuit man being treated for tuberculosis in a Québec City sanatorium, and the 2010 Danish/French co-production Inuk, the story of an Inuit teen in Greenland discovering his indigenous roots.

Native land: The four indigenous-themed features included in this Reeling Back package are director Philip Kaufman’s The White Dawn (1974), Kieth Merrill’s Windwalker (1981), Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves (1990), and Lee Tamahori’s Once Were Warriors (1994).

Already included in the archive are: Alien Thunder (1974); The Inbreaker (1974); The Wolfpen Principle (1974); Black Robe (1991); Clearcut (1991); Thunderheart (1992); Incident at Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story (1992); Shadow of the Wolf (1992); and Pocahontas: The Legend (1995).