Monday, May 12, 1986.

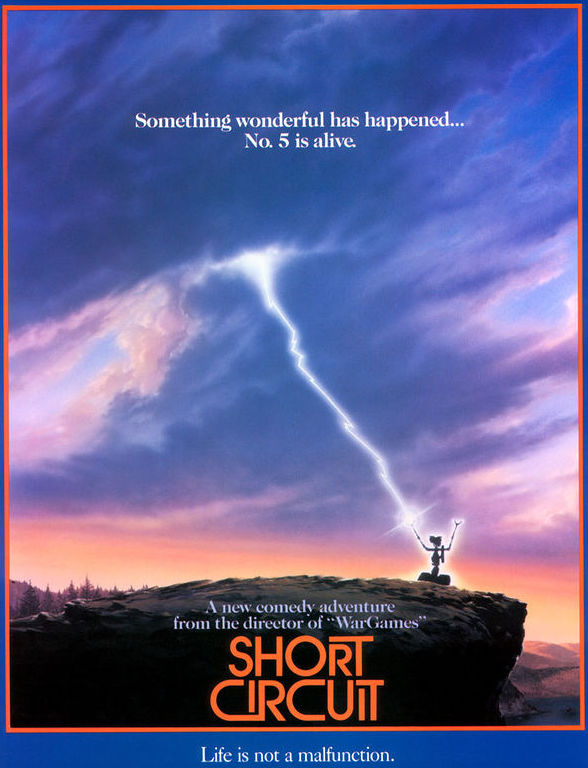

SHORT CIRCUIT. Written by S.S. Wilson and Brent Maddock. Music by David Shire. Directed by John Badham. Running time: 98 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier 's warning: occasional coarse language and swearing.

STEPHANIE SPECK (ALLY SHEEDY) knows that she is someone special. A friend to all living things, she has kept faith with the Ectopian ideals of the 1960s and dreams of a close encounter of the third kind.

Now, standing in the other-worldly light streaming from her own natural-foods Snack Service van, she realizes that her moment has come. “Oh, my god! I knew they’d pick me,” she squeals softly to herself. ''I just knew it . . ."

Director John Badham knows how to keep it light. A filmmaker with a reputation for producing entertaining, successful mass market summer pictures, he is emerging as a man with a consistent, if unobtrusive, liberal vision.

At first glance, his Short Circuit is yet another slick, f/x-oriented E.T. knockoff with Steve (the three Police Academy pictures) Guttenberg and brat-packer Ally Sheedy thrown in for teen appeal. The non-human hero is an $11-million robot soldier known as Number Five (voiced by Tim Blaney).

Five is one of several laser-firing Strategic Artificially Intelligent Nuclear Transports (SAINTs) developed for the American military by the NOVA Robotics Laboratories of Damon, Washington. Following a demonstration of the self-propelled SAINT’s deadly capabilities, Five experiences an unexpected power surge, accompanied by sudden self-awareness.

Escaping to Oregon in search of ''input,” Five meets Stephanie. In pursuit of the runaway killing machine are its creator, the unworldly Dr. Newton Crosby (Guttenberg), Crosby’s faithful Indian companion Ben Jabituya (Fisher Stevens) and NOVA's trigger-happy security chief Chick Skroeder (G.W. Bailey).

The scientists claim that Five is malfunctioning.

“Not malfunction, Stephanie,’’ the mechanism insists. “Number Five is alive . . .”

It's a comedy, of course. As written by former cartoon scenarists S.S. Wilson and Brent Maddock, the human characters are all overstated, the humour broad and the gag payoffs physical.

Indeed, it just might spoil the fun to suggest that Badham's picture is actually a carefully structured inquiry into the nature of life, death and ethical behaviour. Between chuckles, Short Circuit actually has a thing or two to say about what it means to be alive.

No preacher, Badham never interrupts the action to lecture his audience. Even so, his knock-about comedy contains within it something like a catechism, cleverly raising questions and then supplying the answers.

Just what makes Five think that it's alive? At first, it's an urge to self-preservation, then a thirst for knowledge — input — and, finally, something like a sense of humour.

What convinces Speck and Crosby that Five is alive? Along with the filmgoer, they see that NOVA's machine is no longer controlled by its program, but a free will capable of moral choice.

Designed as a weapons system, Five's awareness of itself as an intelligent, living being makes it impossible for it to cause the death of other life forms.

What really brings Five to life? What we're shown is a literal bolt from the blue. What we hear, as lightning strikes Five’s metal body, is the voice of a startled NOVA technician.

“JESUS H. GOD!”

What brings the movie to life is Badham's ability to make such points without ever impinging upon his picture's comic mood. Even filmgoers who don't think about it will enjoy Short Circuit.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1986. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Artificial Intelligence (AI) scares us. Since its first screen appearance — as the Robotrix Maria in director Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi classic Metropolis — the self-aware machine is most often seen as a malevolent threat. HAL 9000 (in 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey) has its own agenda that does not include preserving the lives of his human companions on their voyage to Jupiter. Proteus IV (in 1977’s Demon Seed) rapes its creator’s wife. CSM T-800 101 (in 1984’s The Terminator) is on a mission to destroy the entire human race.

With few exceptions — Huey, Dewey and Louie in 1972’s Silent Running; R2-D2 and C-3PO in 1977’s Star Wars — AI’s were not played for fun. That finally began to change in the 1980’s with the 1984 release of director Steve Barron’s Electric Dreams, arguably the first AI comedy. In it, a personal computer named Edgar becomes involved in a romantic triangle involving its owner and his girlfriend.

And then there was John Badham’s 1986 feature Short Circuit. Critically, I was something of the odd man out in suggesting that the picture had real depth to it. The fact that it starred Steve Guttenberg seemed to rule out any serious intent, and it was easy to see it (as many did) as a throwback to the Disney Medfield College comedies of the 1960s (such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes). Its intent notwithstanding, Badham’s feature was a box-office success, and inspired a 1988 sequel. Directed by Kenneth Johnson and filmed on Toronto locations, Short Circuit 2 really was a lame follow-up to the movie that had made it possible for us to think of AI in the movies in new and creative ways.

Above, I suggested that 1984’s Electric Dreams was the first AI comedy. That movie reworked the plot of Epicac, a short story by Kurt Vonnegut first published in 1950. In 1974, Vonnegut’s tale was adapted to the small screen, one of three episodes in the made-for-TV feature Rex Harrison Presents Stories of Love. The man in the director’s chair was John Badham.

A Bushel of Badham: Today’s five additions the Reeling Back archive celebrate the cinema of John Badham. Included are his 1976 debut feature, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings; the 1981 drama Whose Life Is It Anyway?; the 1986 sci-fi comedy Short Circuit; the 1993 thriller Point of No Return; and the action adventure Drop Zone (1994). And, of course, there is my review of his new book, John Badham on Directing - 2nd Edition (2020).

Wait, There’s More: The six John Badham features previously posted to Reeling Back are his 1979 adaptation of Dracula, as well as Blue Thunder and War Games (both 1983); Also included are the made-in-Vancouver Stakeout (1987), Bird on a Wire (1990) and Another Stakeout (1993).